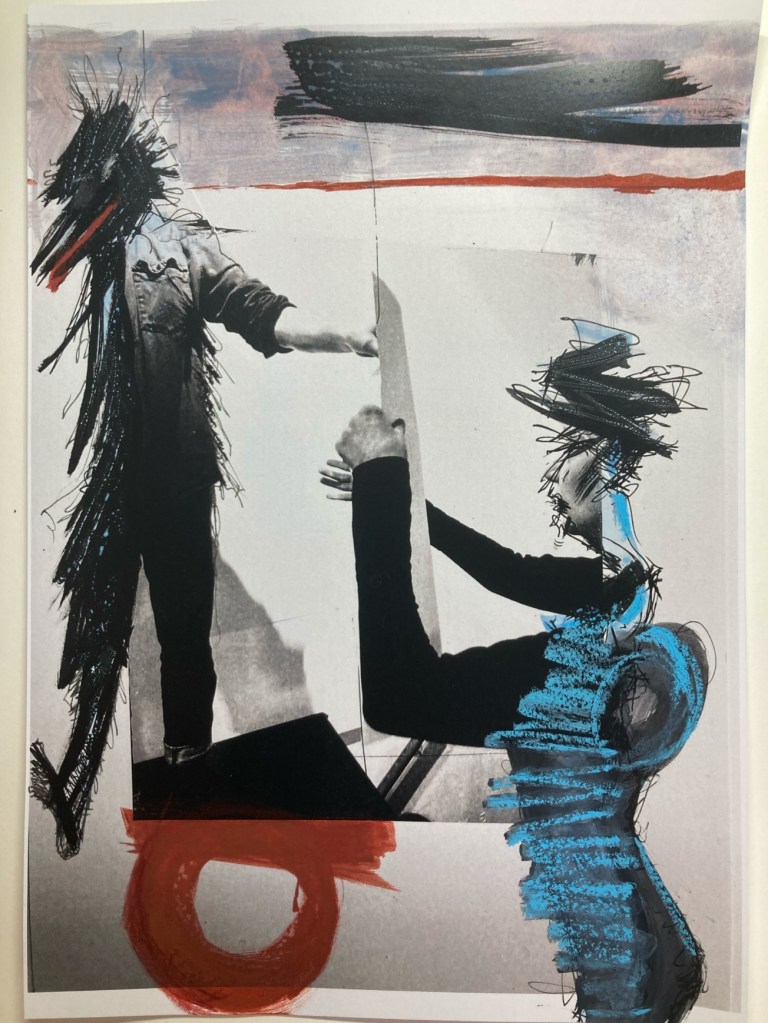

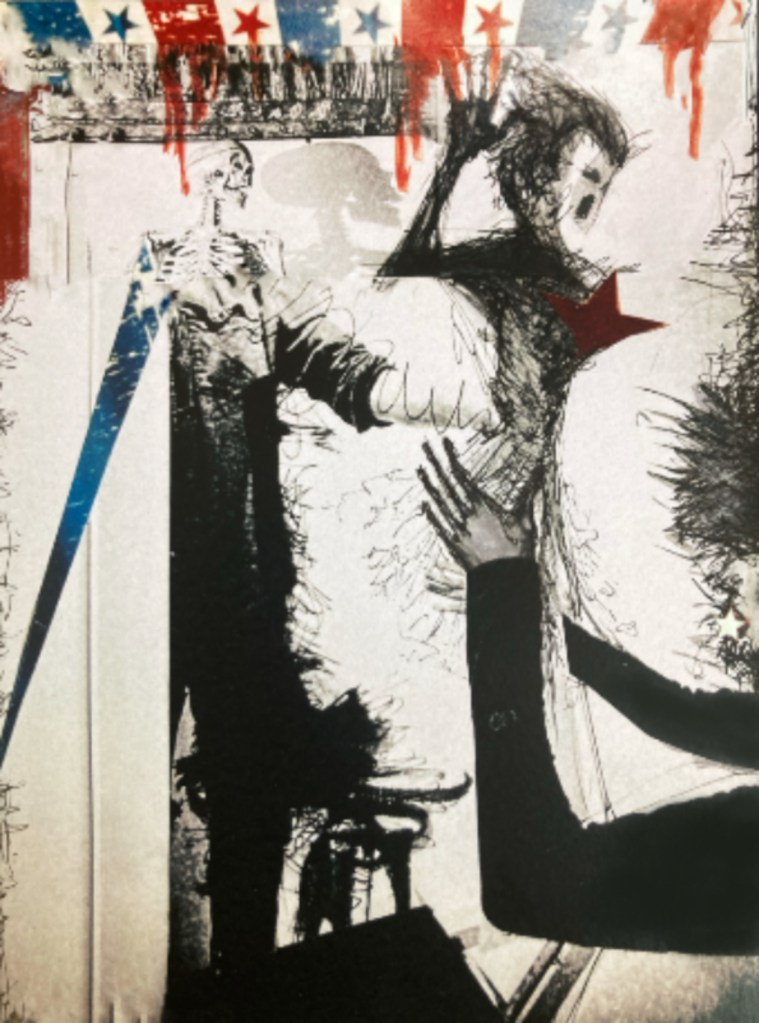

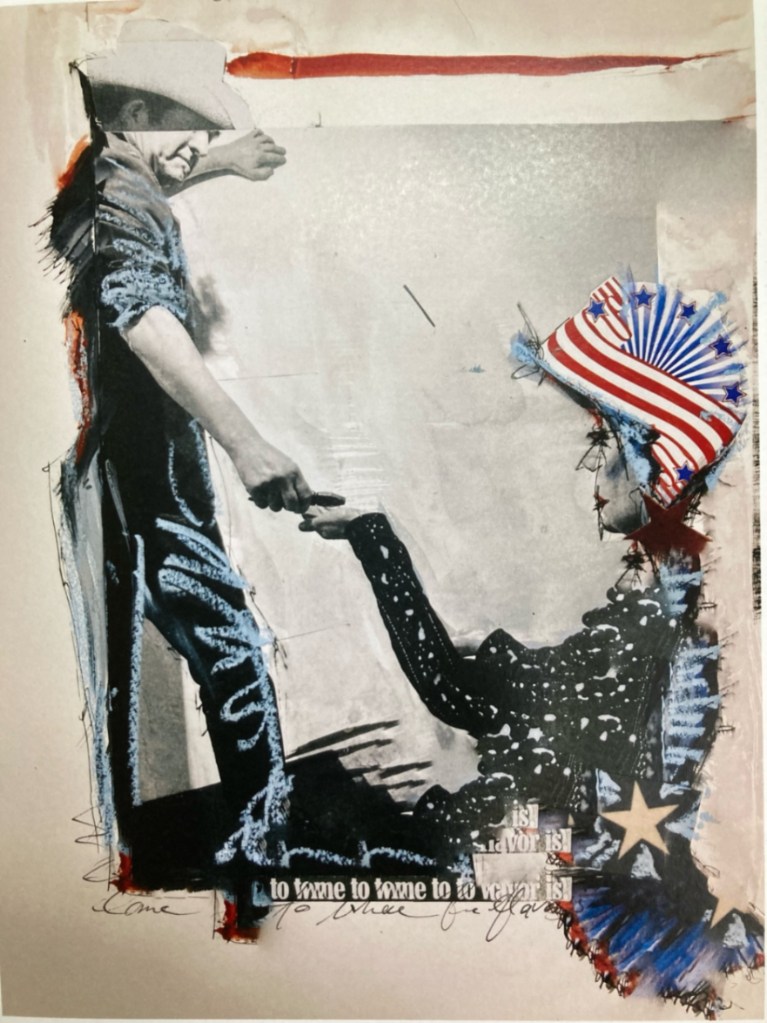

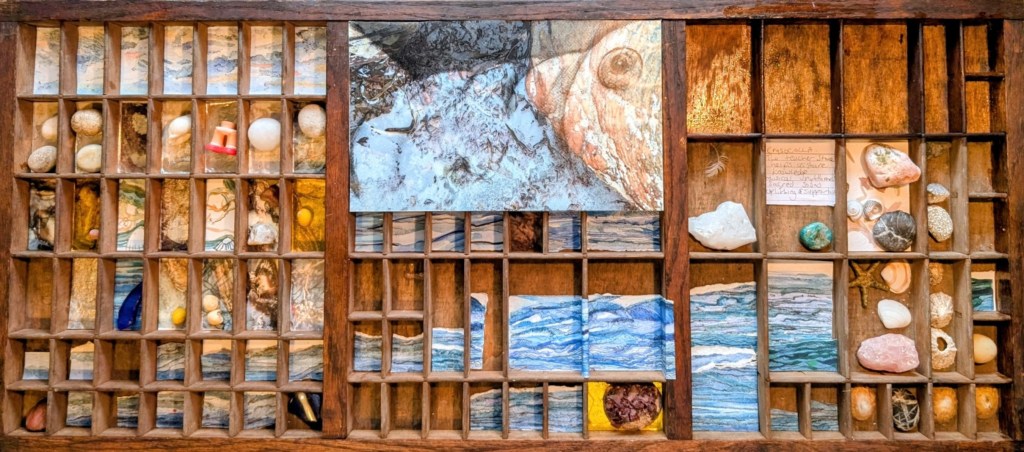

Photo by Bo Mandeville

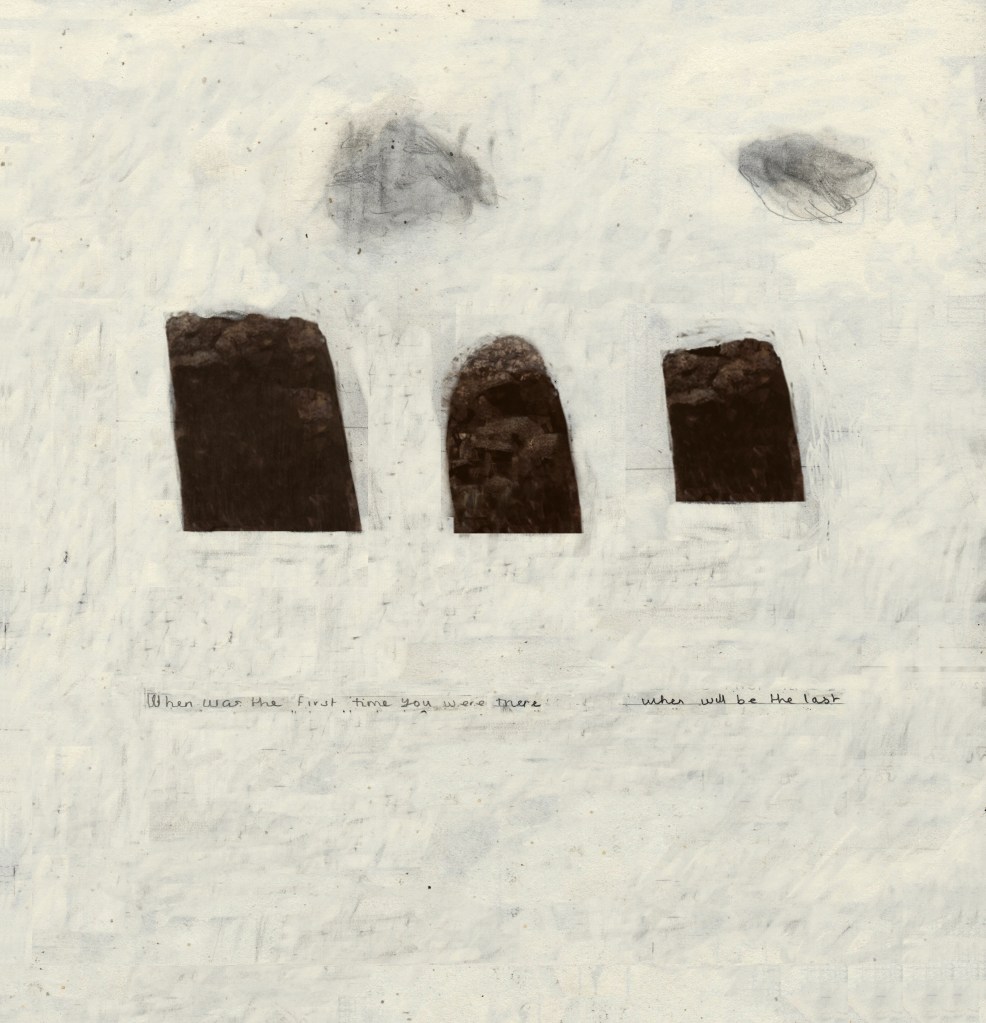

Driving from Edinburgh to Cairnryan, still in a state of dulled lucidity, unable to fully grasp the enormity of the journey. Once boarded, sounds, smells and motion wake me. I notice the dissipating sleep inertia while cruising. I observe how coastlines move along the ferry. Waves delineate the present, allude to the past and possibly a future. In my mind, I draw the shores with cliffs and hills, inlets and rivers flowing. Sketch the clouds too.

Some ancestors endeavoured the same voyage. Probably many times. Perilous on occasion. From Argyle to Antrim. Settling. My family’s history, a fragmented genealogy, has recently become more important to me. I’ve managed to connect dots, milestones and major events.

Forefathers joined rebellions and fought for hope. Romantically perhaps, I wish valorous and chivalrous men engaged in battles to protect the vulnerable and those who couldn’t stand up for themselves. But I know these forefathers — particularly the first ones who crossed from Normandy to lead the charge at Hastings — were mercenaries. Medieval warriors for coin who later became part of more rewarding and legitimate causes. Fights for freedom. Something I like to mention with pride.

Thinking of those many descendants and generations through centuries of being and remaining unsettled. Stories to make sense of my own existence.

The crossing is smooth. Too short for elaborate meanderings. As I never used this ferry crossing before, ruminating through history appeals, is pertinent. Locations as markers of my mariner heritage: Loch Ryan, Carrickfergus and Whiteabbey. An ancient maritime route. Connecting Scotland and Ireland, trading and exchanging stories, for centuries.

Docking in Belfast comes as an interruption. Like the ancestors, who feel so discernible now, this is a brief stay. Layover, a pause. I walk and my antecedents walk with me. Unsteady and slow, vague and opaque. But they are there. Here.

. . .

Reaching Ireland feels like an achievement, culmination of many attempts and struggles. There’s a sense of accomplishment. Finality or not. So…I tell myself this won’t be the last time. Self-reassurance feels like cheating life. And death. Perhaps I have always been a cheat, an imposter — a syndrome that has plagued me since early teens.

I see opportunity for new experiences, even repeats, as a welcome sign, a bonus, a rewarding gift for my own persistence and perseverance. An inherited determination that has possibly prolonged my life, or slightly plateaued the progression of symptoms and appears to have altered the course of expectations, both from the clinicians perspective and our (family and me) own.

“Life expectancy is six to nine years for most. Some get twelve.” It says so on the website, in the leaflets. Nine years in, I sincerely believe I have more than three years left in me. A calculation I have never expressed, never shared. An aspirational awareness.

When the new neurologist affirms the diagnosis — Corticobasal Degenerative Syndrome — he immediately adds ‘atypical’ with a gentle smile, referring to an uncharacteristically slower decline than expected. I return his smile. As if we bond in a complicity to deceive the expected. Gratitude, an element of self deprecation and a desire to cheat the norm. He tells me there’s no certitude, no predictability or any clinical factors to provide a reliable prognosis. But he knows the numbers as well as I do. He too, understands time. And he knows it’s irreversible and incurable, degenerative. Curtains are closing, slowly yet very surely. He knows, he alludes to it and he gives me another, now even more compassionate smile. I like his manner, his tone and expressions, his clarity, his twinkle. A shimmer like tiny stars on dark curtains.

Some use the word gift, as if a benevolent creature rewards me. I accept it all: my condition, the illness, the lack of clarity and certainty of prognosis, the inability to obtain assurance. There’s defiance and acceptance. I resist limitations while embracing an increasingly disabled life.

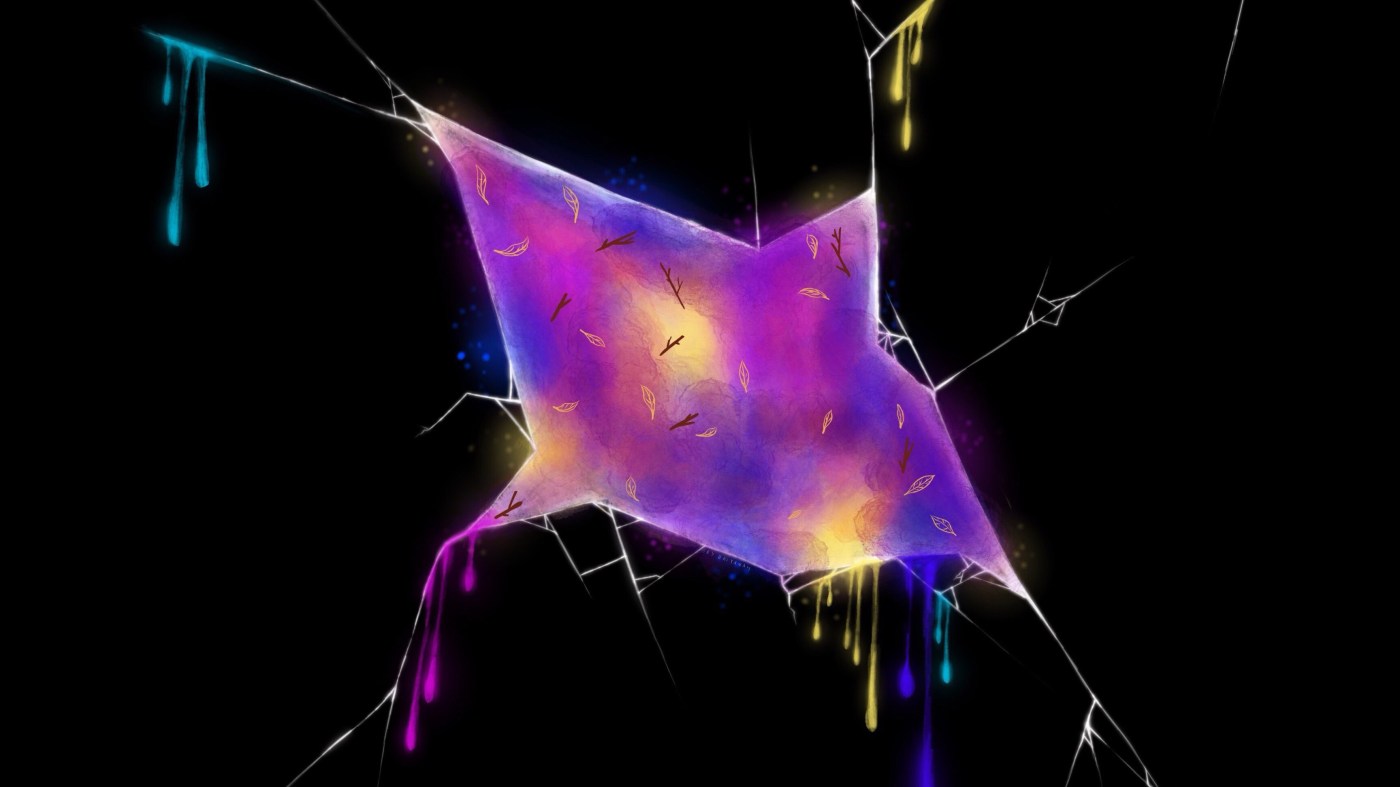

I no longer drive myself. I miss it. The car, the independence, possibilities and destinations. Actually, I no longer have the ability to do much myself. Beyond some thinking. And even that is difficult. For more than three quarters of the hours of the day, I struggle with everything. 75 per cent of the time I exist in near to full obscurity. I live in the vicinity of perpetual fog, my life floating around mist banks. Fog formations over bodies of water with me on a boat without mast or sail, no oars nor anchors. To me this mist, the fog, appears monochrome, as rudimentary woven linen and lace. Écru. Raw and untreated. Weirdly tangible. Veils, retaining some elegance and delicacy, rather than heavy ruby theatrical curtains. They open a few hours each day when I feel freed, am allowed to wonder and be lucid.

Definitely happy. Really happy. Childishly happy.

Despite that, some hours later, I am always ushered back to my veiled sense. An uncertain existence, where all true consciousness evaporates, just leaving some cloud-like space I fill with unknown. Unknowns. Plural.

Repetitive oscillatory motions, erratic pendulum patterns. Yet, I am truly happy.

Embarking on this road trip, I emphatically exclaimed it — “I am the happiest I have ever been.” — unsure if anyone would believe me. And maybe it did sound unreal, not credible, callous even. Surely, key events in my life Have rendered me happier. No! Maybe this is a different connotation of happiness, or as I see it, another realm, a new dimension.

An end-of-life prolepsis, ahead of time. An early fictionalised version, or view, with sea horizon clarity on a bright day. Translucent and floating above aquamarine, turquoise, cyan and seafoam. Tangible glee, near-delirious high spirits I can hold in my hand as tanzanite, reminding me of trichroic properties. Appearances of sea blues, sunset violet, with lavender tones, hints of tangerine, blood orange and burgundy.

It is not contentment, not merely gratification, neither fulfilment nor a feeling of comfort. It is an elevated joy, elation and the discovery of tingling delight. Even a somewhat tantalising notion of new found jouissance, discovery of late life ecstasy. Rather apt, timely. My own renaissance.

As physical excruciating pain has a hold over me, like a threatening hang-man standing on a scaffold not too far away, smiling. Agony always is an ugly face.

When I mention joy and happiness, others often find it impossible to imagine. Maybe because of my facial expression, at times anguished, when muscles jerk and spasm and my entire body is assaulted by torrents of aches.

Or maybe because of the finality. What appears contradictory makes it even more special for me.

The north to south drive crisscrossing counties and sceneries is not so much a reminder of previous returns home, but a refreshing perspective of an amazing varied tapestry of places and meanings. New, old, new, old. Non-linear meaning, circular mapping, a cartographer’s wild dance and rites of spring. Around a fire with flames reaching up as if to colour the night sky yellow to amber. Past autumn, in a brightness of winter. Anticipation of renewal.

Closer to home, it is more recognisable.

Memory-lane is flanked by old copper beach trees whose drooping branches appear to prepare for weeping. Nature’s anticipation of sadness and a reminder of cycles. Limbs surrender. This is not my dolorous time. Not yet. Desolation emerges in shapes from crystalline and fluid to sharply outlined and clear. Coloured or black. Sorrow hangs on branches as a substitute for once vibrant leaves. They all fell and are heaped along the path to form floating ephemeral dams and ditches, they’re soft-walling the roadside but it’ll only take the lightest breeze to displace them. I like the lightheartedness of that thought. Any glumness I might have carried on my shoulders floats away. Anticipatory melancholy instead of deepest darkest grief, is what I note about this lane.

Sweetest melancholy. Pensive and pending in this moment. Slow yet still rhythmic. Poetic and impressionistic vibrant.

While I look at the sky, we’re driving slowly towards the river, swollen as if the banks are no longer able to contain the landscape, flooding the cartographers precision with new impressions. I settle for seeing clouds simply move. Different boundaries. New horizons. Not for me. Or not for long for me. Again, I wonder if cloudscapes, seascapes and landscapes, those I happily contoured or traveled through for decades, are as inviting to generations following the imprints. In sand or dust or ash.

This visit is about letting go. Like clouds. Or feathers of smoke from the wood and peat fire that invites me to sit down. Perhaps have a drink. Smile. Or not. Yes, smile.

Smile…

. . .

In 2013, Bo Mandeville moved from Ireland to North Wales to run the National Writers’ Centre. After less than two years in the post, he had to retire due to a neurodegenerative disorder. Over the years, his multidisciplinary practice has taken him from Ireland and Belgium to France, Netherlands, Germany and the United States. His work spans cultural anthropology, film-making, writing and creating (mainly) anonymous, ephemeral land art. He set up and directed several multidisciplinary arts projects and festivals, curated film events and was a board member of an EU Film Festival organisation. Bo has scripted several film projects, produced and co-directed documentary films and gave talks about film at events and colleges.