tomb speak

black cold damp

spider crawl wall

ant travel cracks

cow eats grass sun

static turns blue

walls turn moon

moss grows soundless

fingers press wall

country left dogs

eyes blink slow

future fact

silence full fiction

warning weight

solar system

regret

water drip

virus spread

body break

pause

catch

quick orbit fast revolution

news

work

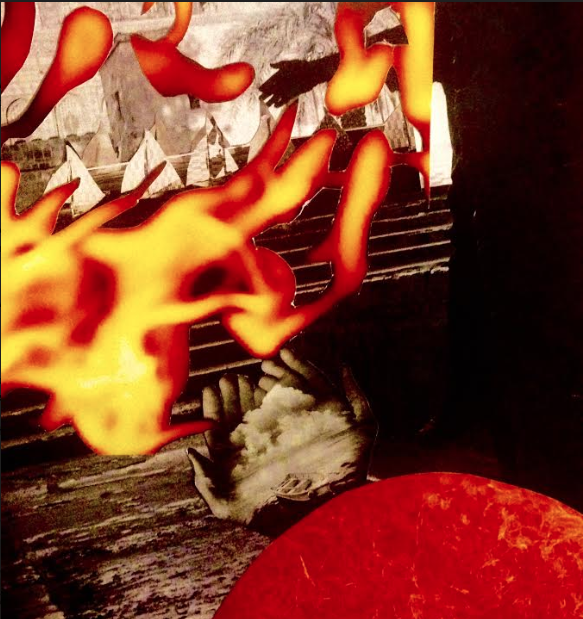

ah ah what do you want from me girl tip toe round my tomb don’t want need enter tomb sit quiet what lies do we tell kin what words play accomplice silence why won’t you let me stay dead we are heavy people dense stars years after your life ends your daughter might sit across the table from her new mother sight some old thing could cause words to spill out new mother’s mouth your daughter with all terms she learned from nuns may feel inclined push back from black of her throat instead she will probably look at new mother practice mercy unable bear strip naked brunt this family’s weight there would be no way there was no way to know tails of supernovas fall heavy and so we should have been able to predict you can kill a person in the midst of pretending to be a god you can murder someone with your godlessness you can end up in big trouble we can keep starting days starting sentences with all things being fair and equal but nothing is fair no thing is equal the only possible way we could be anything like them is if our bodies were to lie in adjacent boxes if our ashes were to settle in respective urns and even then mine might be riddled with bullet holes covered in burns yours emptied of organs exhausted by history there could be rope fibers sticking out of our necks crowns made of splinters as they lie cold peaceful in pearls the whole thing has always been so very boring useless unless someone is willing to give up this ghost what riches to breathe in the dark what kingdom to hold the body in the dark what land do not look for me do not call my name don’t ask me to visit don’t dare ask me to see you hold you forgive you follow you into this deep this so utterly useless descent you don’t know

LOUISE

Sometimes in those quietly enraged moments when I learn of another unreasonable death in this city (NYC) or that city (Providence) or right outside your city (Ramallah) or anywhere in the world, I think of Arwa from your play declaring: “People die every day.”

I often have trouble reading. It starts first with an anxious indecisiveness about what ideas I should be taking in at the moment. This is why I often relent and choose poetry: because the commitment to it is total yet fleeting. The poem plants itself inside you while simultaneously going away from you (a seductive assertion) in ways the novel, which always wants to stay (an attractive insistence), does not. I opened your copy of Louise Glück’s Ararat too late and exactly on time. “A Fantasy” is the second poem in the collection. Its first line made me think of you: because of Arwa who uttered a similar sentiment, because you had read the book at some point in your time of living in Providence and were perhaps speaking to me (at any of the moments you spoke to me) with a little bit of Glück on your tongue as she might have been in your mind.

People do, in fact, die every day. We find ourselves in a global moment where operating forces have staunchly committed themselves to death. We talked about this for endless hours in your backyard on Willow Street. We talked about it walking over the Brooklyn Bridge when you came to visit recently. We reprise those same conversations over WhatsApp and through email. It’s maddening—the audacity, the celebration, the nonchalance of this death dealing. It happens without question and with so much routine—stubborn and unrelenting—that seemingly ordinary people (in the face of this extraordinary death machine) have also become agents of death. In small and big ways, there is so much death, death, death everywhere.

In its natural state, death should be no strange thing. Dr. Andreas Weber talks about this in Matter and Desire: An Erotic Ecology. “Death is unavoidable, but only death makes the world legible. And this language, written in desiring, breakable bodies, is understood by all beings equally.” I find a difficult, but simple truth in this. A life begins and so it must end. This is an important thing to learn. What people like us have learned more quickly, though, is that there are some with such a fear of the fact of this perpetual ending that they extinguish others before their time. On a systemic level, this fear turns into hysteric policy. The extinguishing becomes a calculated extermination: the genocidal tendency. This is when death becomes illegible. It doesn’t make any sense, not in any order of nature, where living beings should be able to abide until some earthly force of Chaos makes the decision on what will end while those who are still living begin again.

What is legible death? Imaginable. Earned. Within the bounds of Chaos. Rendering a single body, and not an entire people, breakable. Legible death would bring forth the possibility of the new, like winter into spring: a collective acknowledgement of the fact of death, a celebration, even! A livability through death that pragmatically insists on life. A refusal of the delusion of immortality.

The deaths we are made to witness are, at once, undeniable and illegible. This fills me with rage. I cannot, in my humane heart, make sense of why this would be happening in a world where I am simply trying to live; and yet, I know, in my human mind, exactly why it happens. It’s impossible to turn away from. There is always another video of a police officer shooting an unarmed person in America, always another photo of someone too young being stabbed to death or ridden with bullets in Gaza, more and more footage of migrants washing up on Mediterranean shores. The language written onto these particularly breakable bodies is the sole desire of other bodies that have made themselves unbreakable by surrendering to the ultimate death machine.Their submission to such a murderous robotization makes it difficult for me to refer to them as human. And why should I if they are the ones who have so willingly disavowed their own humanity?

There is nothing more quietly mundane than the fact that each event of death preludes another beginning. Time starts anew. An “after” commences. This is how and why we have myths. The poems in Ararat feel like an examination of familial myth: how women become mothers who are

mothers until they are widows and the wordlessness—the illegibility—of being a parent who has lost a child. Glück, an observant daughter (as most daughters are), reports from this mythical field in her creation of images, small and still and heartbreakingly apparent. Yes, there is death. But because there is death, there is also beginning. And if there is beginning, that means there is day. If there is day, there is light. If there is light, work will be done. If your work is done, you can rest. In order to rest you must welcome the dark.

It’s so simple.

People who can read death (and who have come to be able to make out—and make it out of—the most illegible of deaths) are not afraid of the night. They welcome it as the only thing that will call their bodies to rest, hoping they will wake in the morning to walk paths that will earn them their ultimate and eternal slumber, praying, with full and tired hearts, that someone else will begin their own work anew.

Diane Exavier @peacheslechat is a writer, theatermaker, and educator born, raised, and living in Flatbush. She makes work about love, loss, legacy, and land. She livetweets basketball games and variously recurring stages of grief.

Leave a comment