I

Millet’s spring mind soared red and skittish as an over-angled kite; in summer it entered the usual back-stall, and by August it had dived low enough for him to have another go at his wrists. This year he made an especial hash of it; fumbling with the false-economy razorblades until he ended up cutting his palms as much as anything else.

Afterwards the ambulance dumped him in the aisle of the A&E, where he lay on the hindmost of a metal spine of gurneys down the building’s centreline. Up on the ceiling, a loose panel exposed a pecking wedge of darkness. He turned on his side; the wall’s blank surface, gouged and spilling brown and fibrous shreds, was in worse nick than his skin.

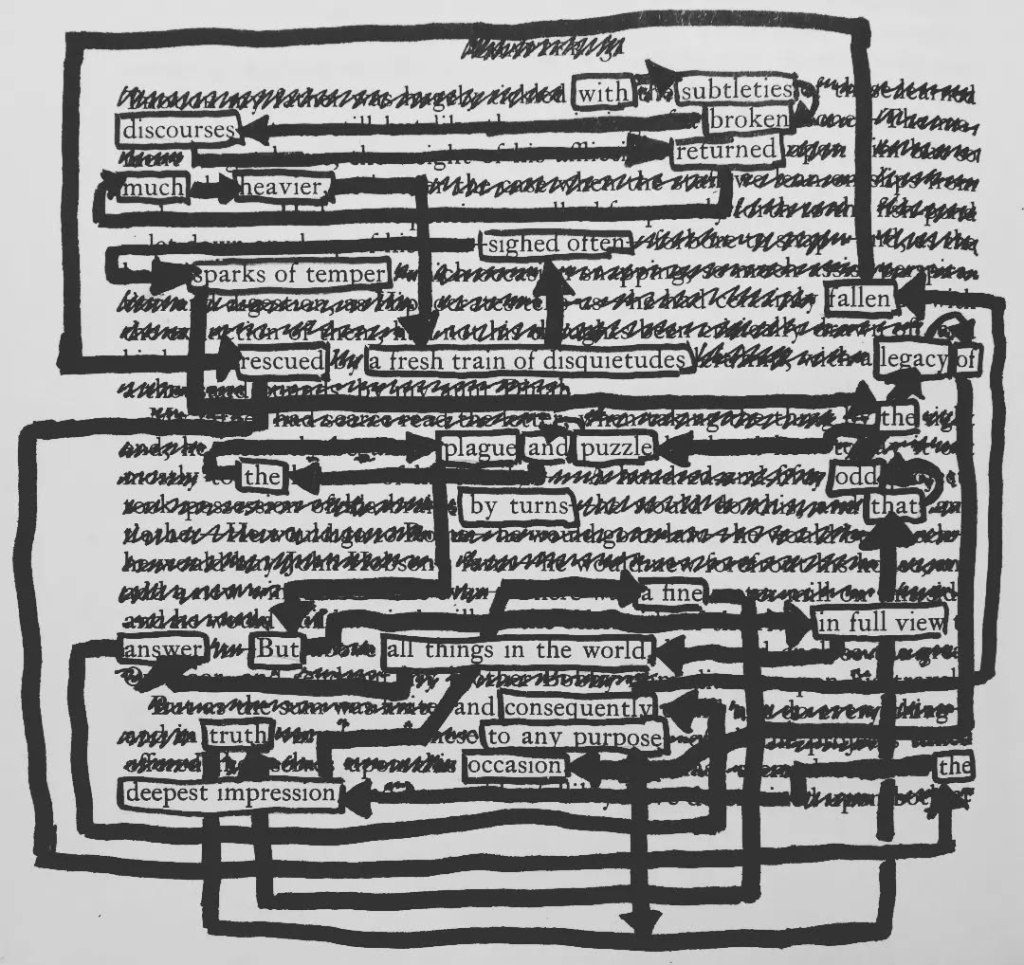

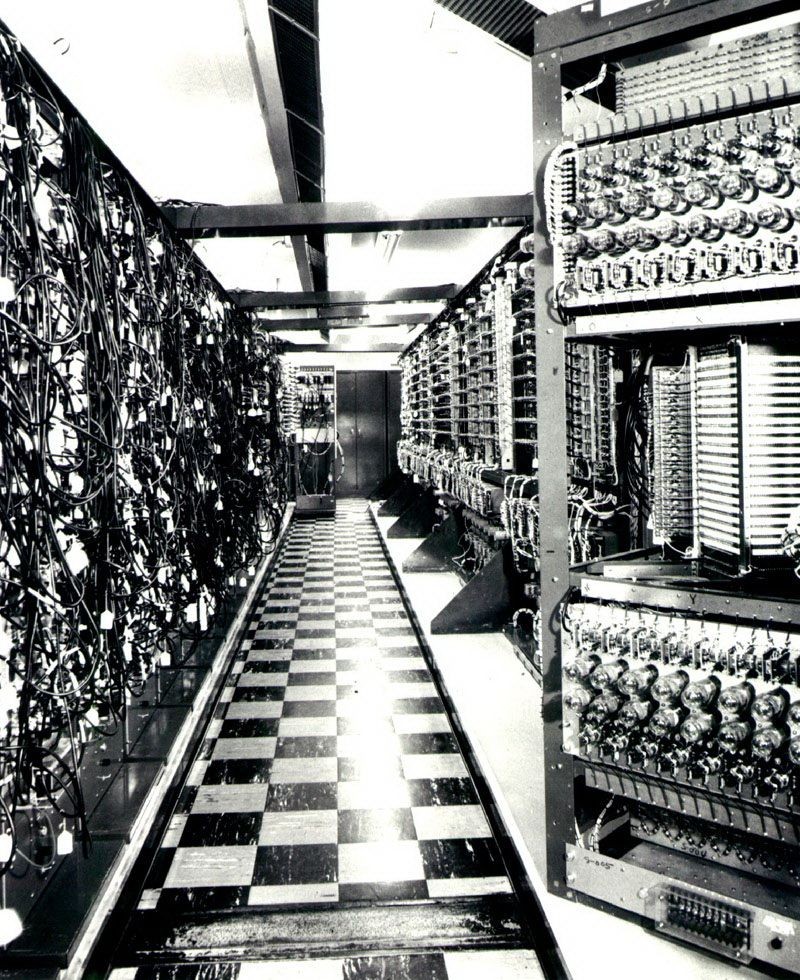

After the stitching they left him in a side room, alone but for the slurping, whistling breaths of someone on the other side of a curtain. Wires snaked around its pleats to a bleeping machine in his own half of the room. His eyes tracked the glowing plots on the monitor; six months after his firing from Aventrix he still couldn’t stop himself subjecting the signals to confused analysis: window functions, discrete transforms, then breakdown into smaller sub-transforms. Radix two, four, sixteen … When the dragonfly lights on the screen began to sting his eyes he gave up his calculations and pulled the bedsheet over his head. Seeking distraction from the thin fabric’s vinegar-and-dead-skin scent, he tried to think its crumpled underside into the hills and valleys of that Stevenson poem. The Pleasant Land of Counter … Counter …

“… pain?”

The syllable repeated, a chain of islands in a sea of blurred speech, and he realized the nurse had arrived, with a prompt to rate his suffering out of ten. He thought the gurney was creaking, some part of the rails extending on either side of him.

“N over two,” he mumbled, and it seemed to do.

II

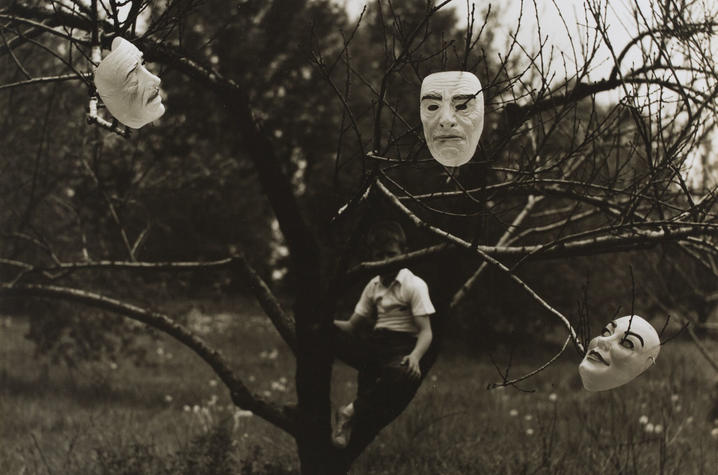

In the morning they had him shower the intact parts of his body. Two quivering shoots of something like watercress poked from the cubicle drain. He hoped they were real; he couldn’t bear the idea of hallucinating such lumpen symbolism. Then he was ferried to a psychiatric hospital on the county border, where his mind banked gently into the institutional mist. He spent much of the next few days contemplating more bedlinen, the troughs and peaks of mountain ranges hugged in soft shadow relief.

He wasn’t so keen on the topography of his outspread hands. In recent months they’d thinned out, the newly slackened skin across their backs trumpeting the onset of real ageing. When he turned them over, the mess of his healing palms troubled him. The scabs didn’t quite match the cuts he remembered making, though his memory was a joke. They kept him well-drugged. Quetiapine, lorazepam. Sometimes in the depths of the night a sister came to shine the round white beam of a pen torch on his eyelids. If they fluttered open, hands offered a pellet of zopiclone, the shadows of uniformed arms beating slowly on the walls. Sometimes, as sleep took hold, his throat felt like there was much more than one pill in it, a smooth, hard, comforting clutch.

III

They began to let him out. First just the grounds, the café and shop, in low outbuildings that reminded him of the old airfield Portakabins. He sat nursing weak coffee, watching the wings of the main building extend into milky light, until one day he and some others were put on a minibus and taken to the nearby riverside park.

On the drive one of their escorts enthused about the new fitness parcours along the banks, with special bodybuilding rigs, Ninja wheels, a machine for chest presses.

“Most of that junk’s already out of order,” his roommate Whitlock confided as they got off the bus. “The screws fail, and they’re a special kind. The council can’t be bothered to replace them.”

They quickly passed the old visitor centre, a silent cube of glass covered in crude paintings of leaf and feather that couldn’t hide the underlying curls of dustsheet. The trail head was marked by a pocked information sign. Lodged in one of its bulges, between a badly-drawn muskrat and a peeling heron, was a cluster of tiny pale green balls.

“They’ve got the map here,” said Whitlock.

“I can see that.”

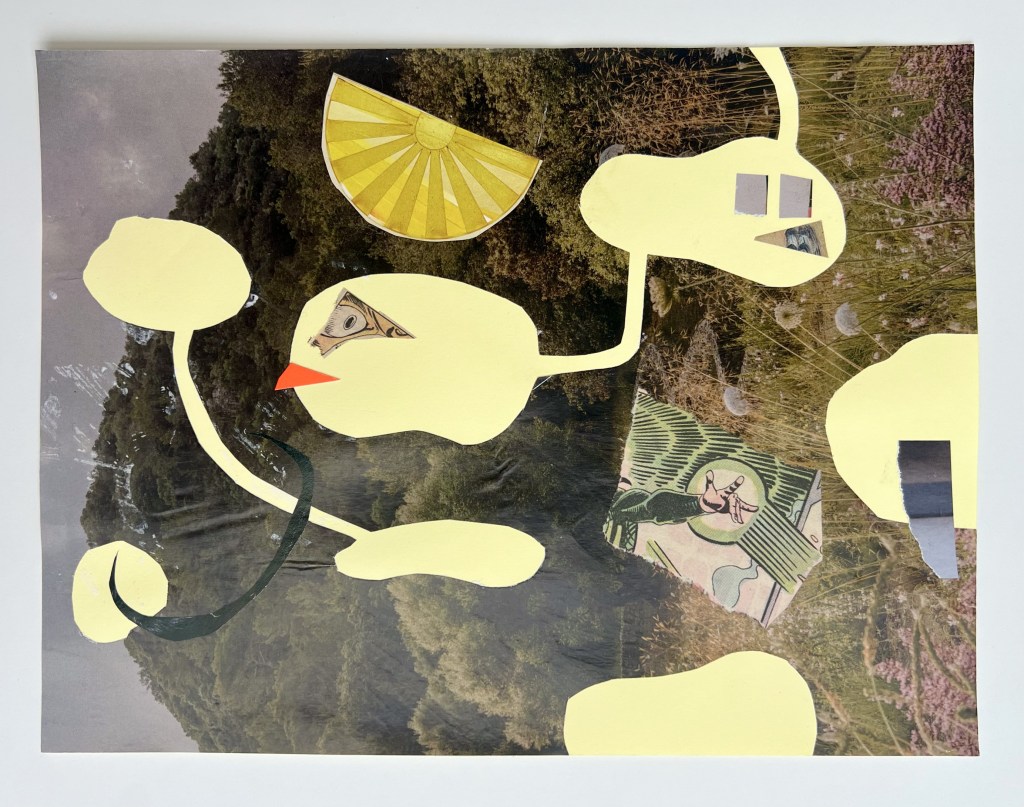

“No, I mean the map butterfly. Araschnia levana, or prorsa, depending on the season. Invasive species, but I’d still like to spot the bleeder. Never set eyes on the black summer form.”

Millet murmured a vague answer to stem the flood of nature facts. The scabs on his palms were itching like hell, much worse than the ones on his arms.

IV

They walked on. After a while he ceased to notice the rise and fall of human voices. To his left was a dazzle of light on winding reed-lined water; foliage encroached on his right. Alder and beech, bramble hordes and white bells of bindweed, parted only by the green metal curves of the fitnessmachines. On each of their instruction diagrams, the silhouette figure looked less like a person.

Finally the path made a swan-neck double bend, and he found himself in front of the most preposterous contraption yet. The paint on this one had almost entirely flaked off, exposing a tall structure of rust-brown metal crisscrossed with streaks of faded cream. It was studded with appendages, and a maze of gears, flanges and blades, culminating in something like a giant upturned wishbone. The sight of the two symmetrical handles fanning out on either side of a discoid seat prompted a distant memory of gym adverts, and then he saw the instruction diagram, with its caption:

BUTTERFLY MACHINE

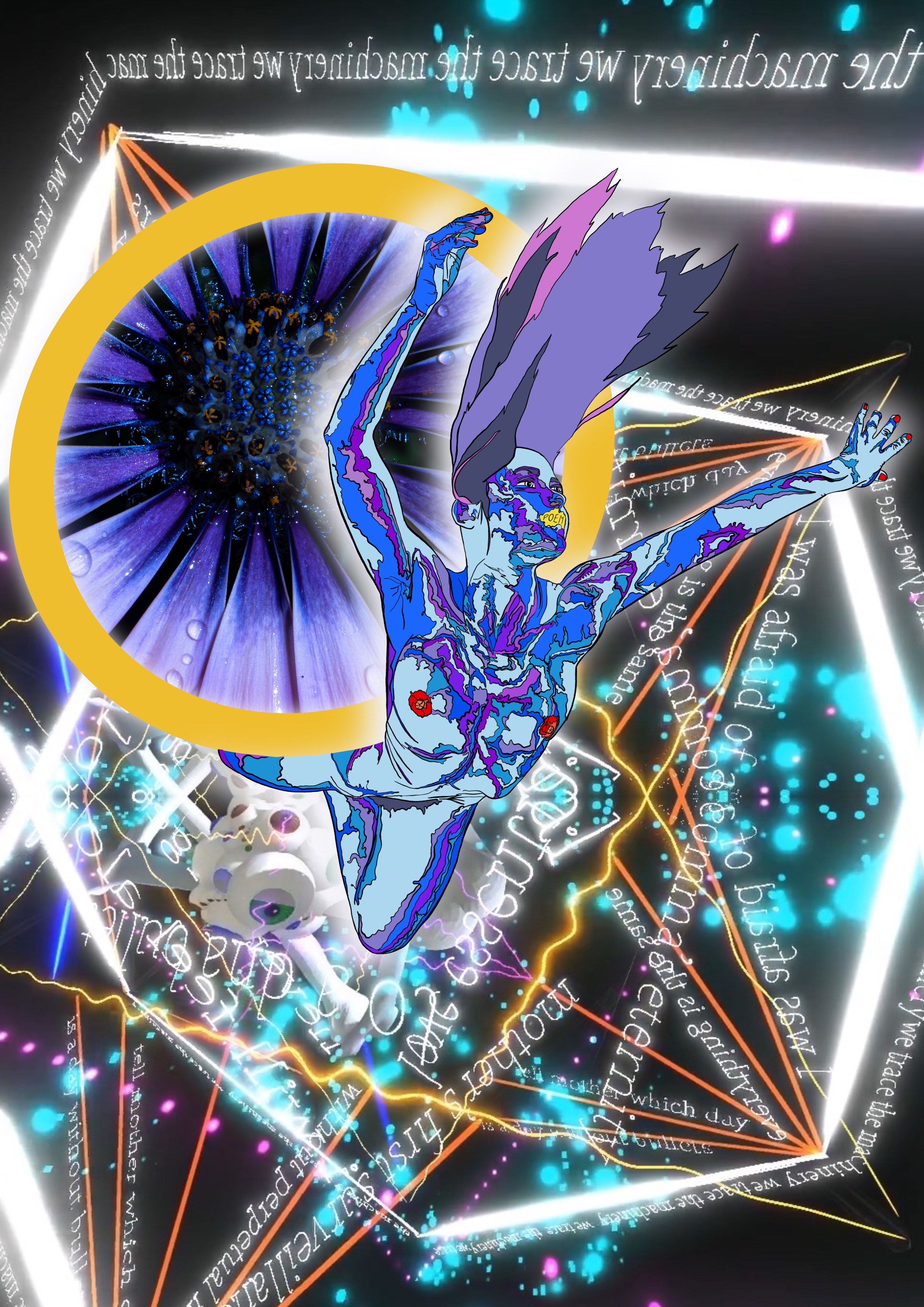

At the sight of the wonky grid pattern running across the underside of the depicted creature’s wings, the scabs on his palms raged until something in him hatched. When he sat down and grabbed the handles above his head, he felt the fire in his hands drain out into the cold metal. Warming it. Informing it. Loading the chart of his scars into its central navigation system. The antennae slewed and thrummed; great metal wings unfolded with a shivering clang and began to beat, then it bore him into the air.

V

Sounds rose up from the riverbank, individual screams convolved into a single wavering keen, but he couldn’t have looked down if he’d wanted to. When the machine broke through the clouds, it dropped its payload of eggs. As they whistled towards the earth he let go of the handles and the craft itself fell away from him. He hung for a second in the air, hands whipped aloft, before each palm burst apart, discretizing again and again into clouds of tiny flitting things; after a moment his mind followed suit, merry black thoughts whirling up to the sun.

Daisy Lyle is an engineering translator & dark fantasy writer based in Normandie, France. Bluesky http://@novembergrau.bsky.social