Nico, New York, 1970 by Brigid Berlin.

Earlier this year, I was asked to discuss Nico for a film to accompany a version of Femme Fatale on an album released in support of the Teenage Cancer Trust.

I talked on camera about my friendship with Warhol silver Factory photographer Nat Finkelstein (his picture of Lou Reed features on the back sleeve of the VU and Nico LP), who I stayed with in NYC over one crazy summer in the 80s (fictionalised in my novel Looking for a Kiss). He hated most of the Factory crowd, but respected Nico. I also talked about the strongest version of her voice – a new poetry of bleakness and sorrow – found on Janitor of Lunacy from the LP Desert Shore; and the pre-historical pagan magic (definitely disorderly magic ) that filters up in Evening of Light – my favourite Nico song – soundtrack to a short 1969 film featuring a young Iggy Pop by director François De Menil.

I also asked: where do the midnight winds go?

And I thought, and still think, about:–

Chelsea Girls on a slow/fast loop, with screen-printed souls, silver fluorescent haze, ghosts of Superstars in broken looking glass. Femme fatale in a turtleneck of shadows, lip-curl velvet, existential bravado – Nico; the kind of person you meet, in whatever way, and emerge transformed to some degree.

Beat drops. Patti-Smith bite. Siouxsie eyeliner like a midnight scythe. Clash-cut rhythm, downtown hymn – 1976, first time her voice slid into my room – contralto made of smoke, from ash and cathedral shadows – a voice too low for the baby-girl 60s, too dark for the sunshine pop factories. A voice like the world’s last cracked prayer.

Old Europe twilight. Disorderly Magic forever.

Nico sings like snowstorm silk, atonal, androgynous, thick with centuries, thick with Dresden flames impossible to forget. Wearing beauty like an insult and tossing it away like a match – one that lit bonfires. Beauty denounced as casual tyranny – darkness as armour, mystery as oxygen. Feeding flames.

And style as wound, wound as song, and song that can outlive every/any man who ever tried to claim/tame/shame.

Iggy said she taught him Beaujolais and art-school tricks disguised as lullabies. He filmed her in a field for Evening of Light, a crack-between-worlds moment where mandolins ring to viols singing, and the midnight winds land as warning. Berlin-ashram meets Michigan-gutter. Music collapsing into beautiful violence. A tribute wrapped in awe, and regret, and the kind of affection and affectation, too, that can only exist between two people who might survive, for however long, their own mythologies.

A shining light for every singer who ever needed to drop their voice below pretty, or permission; or anyone who felt that a woman doesn’t need to shine to illuminate; and who treats beauty as something breakable, burnable, something you could set down and walk away from without saying how very sorry you are; above all anyone who wants a different way to carry their own shadow.

And I am hearing dreamscapes full of dark echoes and erotic street energy. Cosmic ennui that reflects the myth back to the crowd like a funhouse mirror. In a voice that comes from somewhere deeper than the throat – somewhere prehistoric. Silence that knows too much. Whispered in harmonium breath and lullabies sharpened into razors.

Midnight winds circle.

I am also thinking 60s/70s Avant-Garde/Berlin School harmonium drones, tape hiss, proto-industrial rich deep minimalism, European nocturne atmospheres. Cold wave pulses, cabaret limelight dimmed, war-memory spectrality. All of it transposed over the years to Ibiza, New York, Los Angeles, London et al as a poem that moves like a Super-8 reel found in a basement in Kreuzberg, or somewhere like that. Yes, begin with a hiss. Analog snow falling across a broken tape. A low oscillator trembling. A train leaving some empty cold station at 3 a.m. – slow, metallic.

Then: contralto voice carved from coal-dust. The sound of a city learning to breathe after the bombs stopped but before the memory ever could.

Pulses flicker – messages to forgotten futures. Where the streets are half dream, half gaping wound, and art is the only currency. Reverberation as survival strategy.

Christa Päffgen, with Factory scars under her coat, Warhol apparitions, spirits and spooks deep in her pockets, and a harmonium strapped to her soul as life and death-support machine. Dressed all in black because colour is hope, and hope is sin.

This is not pop. This is architecture. Built from absence, steel, and memory, perhaps. Nico steps into the drone. War Memory as Original Drone. Repetition becomes revelation. Revelation as trance. Grammar of ruins turns into ritual.

I thought, and am thinking, about slick pavements, streetlamps rattling and failing like old ballroom pianos struggling to project their tone. In the silence between footsteps you can hear the rumour that darkness is not the absence of light but the cradle of it – and that some voices do not break – they remain unbroken, untranslated forever.

Where do the midnight winds go? To the end of time, of course, honey, to the end of time.

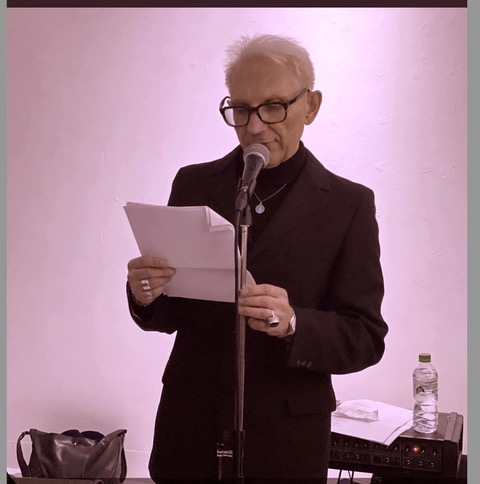

Richard Cabut is a London-based author, whose CV includes the sister books, the popular work of modern literature/poetry Disorderly Magic and Other Disturbances – ‘subterranean scenes, picturesque ruins, neon glowing, Chelsea Girls, the damned, the demimonde, the elemental, being on the edge of being pinned down by our ghosts’ – and Ripped Backsides (both Far West Press), a dreamlike, dislocated and fragmentary Situationist drift through the noir cities. Also, the Freudian 80s cult novel Looking for a Kiss (PC-Press), which has been adapted for screen. And, Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night (Zer0 Books).

He’s also a journalist – ‘NME, BBC, anarchy’ – a former punk musician, a cultural theorist, playwright and long-time chronicler of the underground. richardcabut.com