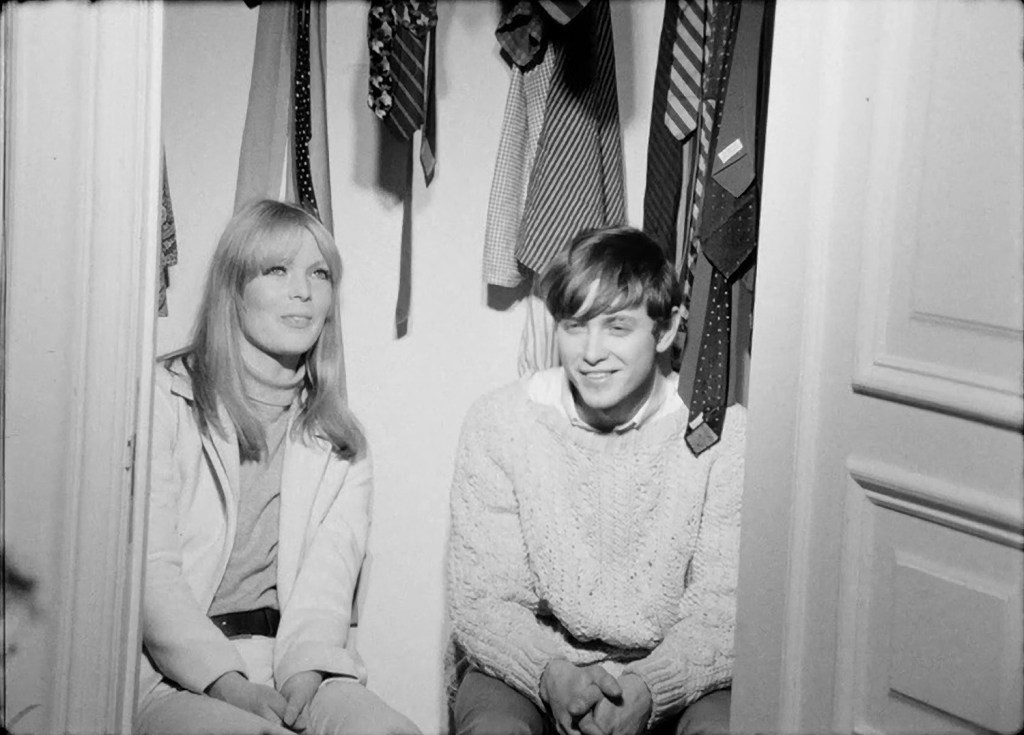

Nico and Randy Bourscheidt in The Closet (1966)

The Closet (1966) was Nico’s first film with cadaverous Pop Art visionary Andy Warhol and thus represents her cinematic unveiling as a Warhol Superstar. It would be a fruitful relationship. As the Factory’s inscrutable Garbo / Dietrich equivalent she would star in several more Warhol films (most famously Chelsea Girls (1966)) while also featuring as chanteuse for Warhol’s proto-punk “house band” The Velvet Underground.

The Closet’s “plot” is absurdist and minimal: a couple living in a closet kill the time (they make small talk, split a sandwich, share a cigarette, kvetch about their cramped surroundings) and contemplate leaving but never do.

For the first few moments the camera is focused on the exterior of the shut closet door in grainy black and white as we hear only their voices (audible but muffled; in fact the sound remains muffled for the rest of the film, poor sound quality being a stylistic trademark of Warhol’s films at the time). Creeping horror that the entire 66-minute film will stay like this is averted when the door belatedly does open and we are finally permitted to see Nico and leading man Randy Bourscheidt (a cute, preppy art student-type) seated inside the closet surrounded by hangers, ties, clothes, etc. While the couple talk or sit in silence, Warhol’s camera either sits totally stationary or prowls restlessly and randomly.

The film is unscripted: instead, we get an improvised, wandering conversation between the duo who have obviously been instructed to ad-lib for the 66-minute duration. Most Warhol Superstars were amphetamine-fuelled, garrulous motormouths and exhibitionists; Nico and Bourscheidt are atypically more reticent. Both seem shy and hesitant, and their conversation is often stilted but characterized by a genuine sweetness on both parts. Some viewers have deciphered the hint of a physical attraction between them which is complicated by the pretty, long-lashed and collegiate-looking Bourscheidt’s apparent homosexuality (The expression “coming out of the closet” was already in use in the 1960s and could be a relevant coded meaning to the film’s title).

Certainly Bourscheidt seems dazzled by Nico, which is understandable: The Closet presents her at the height of her flaxen-haired beauty. It also reveals the complexity of her persona. The performers in Warhol films are essentially playing themselves, so The Closet is a snapshot of Nico the woman at this particular point in her life rather than an actress performing a role. She looks like a statuesque Nordic Amazon but is wispily spoken, reserved and uncertain rather than intimidating or forbidding — her sweetness dispels the cliché of Nico as ice maiden. And her voice – routinely described as guttural or “Germanic” – is infinitely softer than you expect.

As an avant-garde filmmaker Warhol withholds most of the conventional pleasures audiences expect from films (narrative, character development, editing, technical proficiency , etc) but with his Superstars in lead roles he does provide one of the enduring attractions of film-watching: scrutinizing beautiful people. So, while “nothing happens” in The Closet, we do get to appreciate the physical attractiveness and hip wardrobes of both Nico and Bourscheidt at great length. Nico wears what was then her signature look: an androgynous white pantsuit, turtleneck sweater and boots combo that would be the pride of any Mod boy, feminized by a curtain of long blonde hair.

Nico would have been in her late twenties by the time of The Closet, and Bourscheidt (at a guess) between 19 and 21. She speaks to him in tones that shuttle between maternal concern and big sister-ly teasing. Both seem vaguely embarrassed and self-conscious on screen, but unlike Bourscheidt Nico possesses the poised armour of sophistication: by 1965 she travelled the world as an in-demand fashion model, spoke several languages, acted in films like La Dolce Vita (1959) and Strip-Tease (1963) in Europe, was the mother of a young son, and had started her singing career.

In addition to this hauteur, Nico utilizes her experience as a seasoned model: she is clearly un-phased by the camera’s roaming gaze and is skilled at graceful self-presentation. She has a neat trick of looking down moodily so that her long blonde bangs obscure most of her face and then suddenly looking up and tilting her head, dramatically revealing sculpted cheekbones, Bardot lips and sweeping false eyelashes.

“Are you afraid of me?” Nico suddenly asks Bourscheidt towards the end of their awkward filmic encounter. He looks startled and doesn’t know how to reply. “I’m not trying to embarrass you!” she assures.

At the film’s conclusion Bourscheidt teasingly asks Nico if she’s forgotten his name. Indeed, she has, and tries to cover by asking him, “Is it Romeo?” He says no and she answers, “Why not?” He asks if she wants him to be Romeo and should he get down on one knee. She replies, “Oh, no. You be Juliet and I’ll be Romeo.”

Like the Shangri-Las song, Graham Russell is good-bad, but not evil. He’s a trash culture obsessive, occasional DJ (Cockabilly – London’s first and to date, only gay rockabilly night), and promoter of the Lobotomy Room film club (devoted to Bad Movies for Bad People) at Fontaine’s bar in Dalston. As a sporadic freelance journalist, over the years he’s contributed to everything from punk zines (MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, Flipside, Razorcake) to The Guardian and Interview magazine and interviewed the likes of John Waters, Marianne Faithfull, Poison Ivy Rorschach, Lydia Lunch, Henry Rollins and Jayne County.