The Taste of Gin

by Elliott Gish

Someone is crying in the next apartment. Genevieve can hear them through the walls, which are thin, but she cannot tell who is crying, if it is a man or a woman or a baby or what. No words, just a thin and liquid wail. It goes on and on without breath, as though whatever makes it is beyond the need for oxygen.

The sound makes Genevieve want to kill herself. Not for any empathetic reason, but because she has been awake for so long and sleep is nowhere in sight and the crying means that it will take longer to arrive.

She sits alone in her apartment, which is very small and bare and clean. She is always alone. The clink of ice cubes in her glass is a comfort, and the smell of gin, and the light of the television. She watches it without sound these days, content to let the pictures wash over her. It is far more pleasant to look than to listen, to sit in silence in the company of light and shape, without the added confusion of story. Story does not matter anymore.

“If it ever did,” she murmurs, and takes a bracing sip. Funny, how much juniper tastes like sap. The fresh tang of pine forests invading the enclosed safety of her home, where all the air has been in and out of her lungs time and time again. Her body has strained it, purified it. She likes to think of it that way—that there is something about herself that has made the air better, like those fresheners they plug into walls.

The apartment is one room, not counting the little closet of the bathroom, and that room contains a bed, a round table with one chair, a couch, and a television. The bed is made, the chair pushed firmly into table. She cannot remember the last time she sat at it—the table—or laid down upon it—the bed—although she knows that both have happened, in the past.

Had there been someone there in the bed with her once? Had there been another chair at the table, long ago? She should know, but she does not. There is a hole in her mind where the knowledge used to be, an empty space that the air moves through.

At any rate, now it is just her. Just her, the small room, and the man in the corner.

The man has been there for many days. He is featureless, dark grey. She does not know his name. He does not have a face. But she thinks that his head is turned in her direction, watching her. The way she watches the television.

It is better not to see him, she thinks, although she cannot explain this thought to herself. No matter. She stopped explaining her thoughts a very long time ago.

There are people on the television making faces, and laughing, and shooting each other, and eating ice cream, and the colours are bright and the movements are quick and it soothes her to watch them go about their lives, safe behind the glass of the screen. It is better this way, without the sound. Sound distracts her, like the crying from next door.

The man in the corner tells her something, or tries to. The words do not come out like words, but bursts of static fuzz that make her hiss in pain. The noise, all the noise, noise, noise, noise!

Someone said that once. She thinks it was on the television.

The people in the screen are her friends, because they are only colour and light. The man in the corner has no colour and no light. Therefore, the man in the corner is not her friend.

“I don’t see you,” Genevieve says, and the person on the other side of the wall is crying, crying, crying, and she wishes she had a gun that she could use to shoot them. They make so much noise, other people.

Her stomach growls as she watches the shapes move. Is she hungry? She cannot tell. Some nerve connecting her brain and her body seems to have snapped. Its needs are foreign to her. That, Genevieve suspects, is why she cannot sleep.

She cannot remember how long she has been sitting there, how long the person in the next apartment has been crying. She cannot remember a lot of things. But she remembers that she likes the taste of gin.

If she keeps her eyes on the television, she can see the man in the corner out of the corner of her eye. He is not approaching her, not exactly—his legs do not move, his arms do not either—but still, he seems to get closer and closer all the time. Or else he is getting bigger—stretching out like a shadow at twilight, pulled out thin and dark.

There had been someone, hadn’t there? Someone who had watched television with her, who came to bed with her at night? Someone who had kissed her forehead and poured gin into her glass?

Whoever they were, they had probably liked the sound of the television. No wonder they weren’t there anymore.

If the man in the corner keeps growing, Genevieve thinks, he will crowd the whole apartment. He will breathe in all the air that she has purified with her lungs, all the oxygen mingled with tiny parts of herself, and he will make it dirty.

“You keep back,” she says, hating the sound of her own voice, the way it rips the air to shreds, but the man in the corner does not listen.

If he keeps growing, soon he will be right beside her, close enough to touch. To kiss her forehead, and pour gin into her glass, and carry her tenderly to the bed. Which is made. Which is neat. Which is ready.

She realizes, as he reaches for her, that the person on the other side of the wall has stopped crying.

Elliot Gish s a writer and librarian from Nova Scotia. Her short fiction has appeared in The New Quarterly, The Ex-Puritan, Grain Magazine, The Dalhousie Review, and many others. Her debut novel, Grey Dog (ECW Press 2024), was shortlisted for the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction and the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize for Literary Fiction. Elliott lives in Halifax with her partner and a small black cat who may or may not be her familiar. Bluesky, www.elliottgishwrites.com, (she/her)

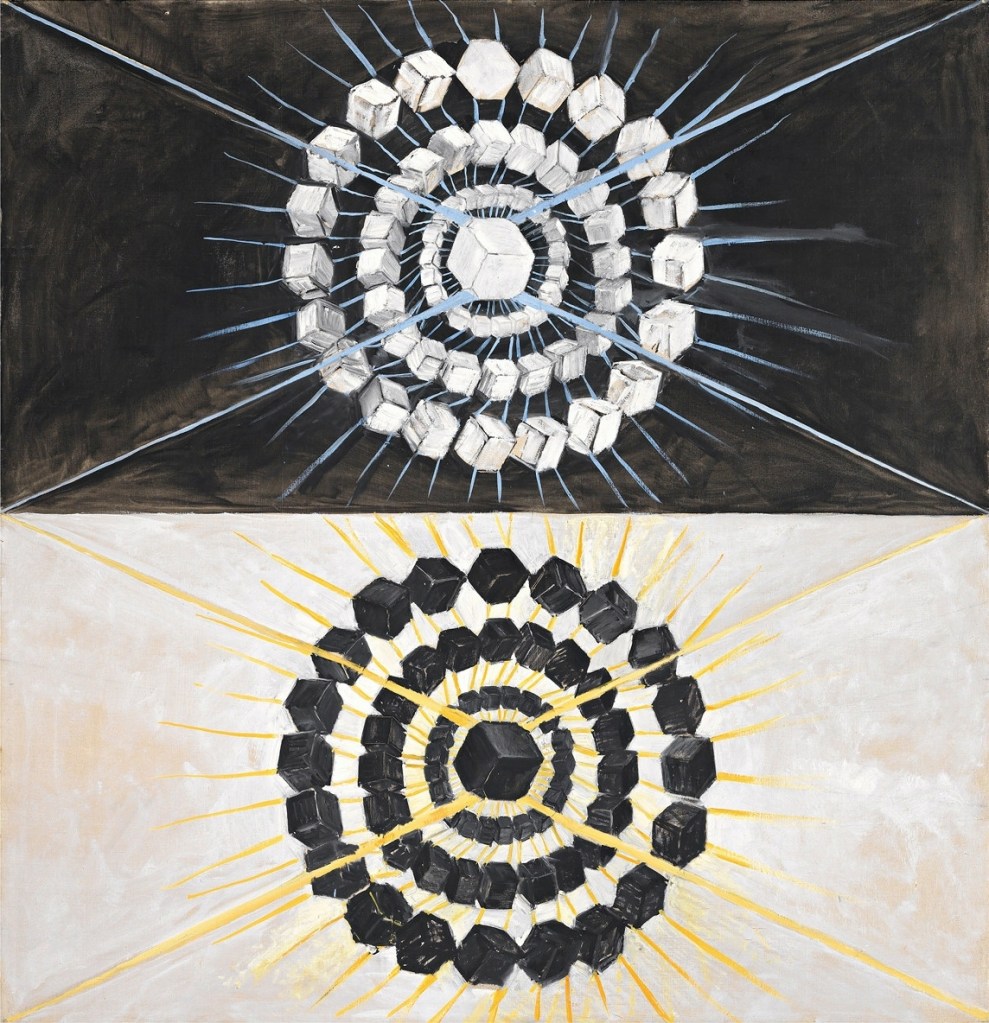

Image credit: Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944) Group IX,SUW No. 8, The Swan, No. 8 (1915) Artvee.com