Photo by Caroline Stockford

Once you see past the cellophaned shop-window of tourism and into the infected stomach-wound of political history you begin a journey to the centre of dictatorship. And you’re likely to survive. Because in their eyes you are a mere fly on the wound, spinning on the spot, feeling sick and having to suck it all up. They might feel an occasional tick at the discomfort of you’re reporting all their business, but with a quick swat, the threat of being locked up, they will send you packing. Off you fly back to your country. You’ll soon be back again. You’ll come because the scent of such drama and the chance to ‘make a difference’ is so seductive.

You will climb into airplanes and out of airplanes, stand in queues at airports listening to psych rock on repeat to make it seem cool to be wearing a suit. You will walk into climates where heat makes a sudden pass at you. The hotels will have terraces descending to cake-crumb concrete, ornate cities choking politely below you. You will blag free afternoon tea in the hotel where Agatha Christie disappeared. You will do this for years and years. Buoyed on the beauty of this city, by the people from whom you learn the meaning of solidarity.

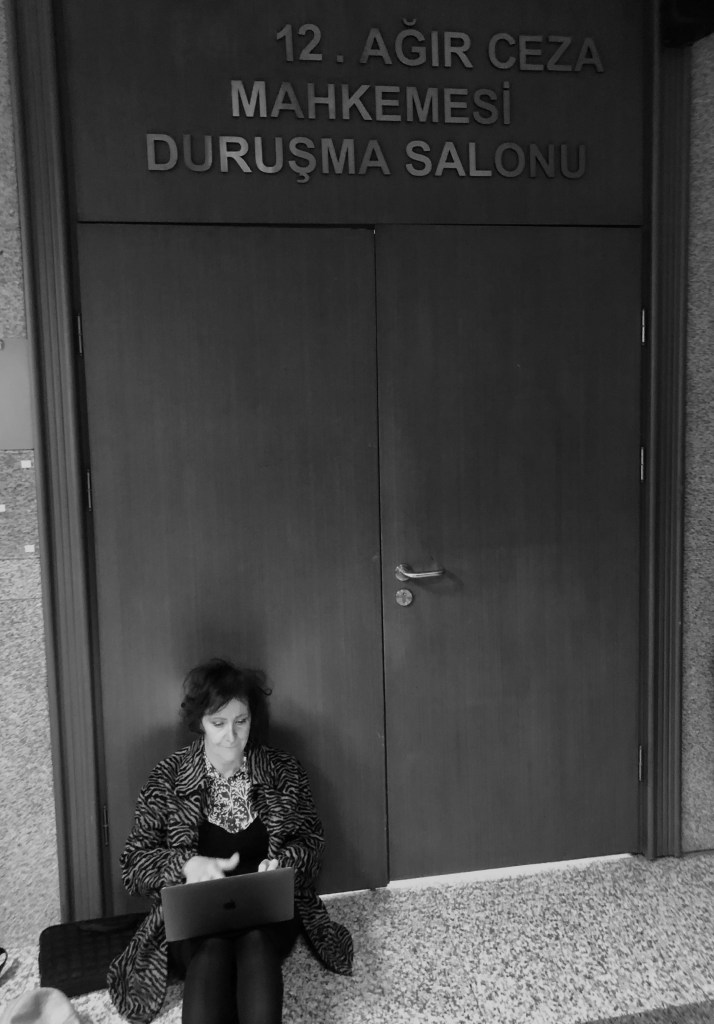

You might go to courthouses larger than a demigod. Where justice is not just blind, she’s in intensive care. Every now and then, to fool the concerned Specialists from overseas at the bedside of Democracy daughter of Anatolia, there is a blip on the heart monitor in the form of a ‘good’ decision from the Constitutional Court. Everyone from Europe nods and puts a tick on their clipboards, smiling at each other from behind the surgical masks.

The British and French have scalpels in their pockets, just in case they get another chance to make choice cuts. It’s all they can do not to dot lines on the flesh, “Je vous en prie, madame mais j’ai l’envie de vos cuisses remplis de l’huile noir dorée.” They want to take her back to last century. She is confused and they all think she’s easy. She has had a lot of lovers in the past. They think they can own her just like Croesus tried but those silly billies don’t even know her real identity.

While Consultants from the EU compile assessments on the health and usefulness of the patient, the rats go on eating the body from underneath the bed. Small regional judges rebel against the Supreme Court. The government opens cases against the Istanbul Bar. Everyone visiting agrees the patient looks passably robust if you just don’t get too close.

The brochure that prompted your journey to the centre of dictatorship will be social media posts showing Kurdish boys dead on barricades and their families looking out from front windows, prevented from collecting their corpses due to sniper fire from the Turkish state. Dogs devour sons’ bodies near the door. You’ll see four old people, wearing white and waving flags be gunned down as they sneak out with a stretcher. Neighbourhoods and a city flattened by airstrikes and tanks. Sur, Cizre and the walls of Diyarbakır. It was 2016, just nine long years ago.

You’ll stand up, then, in your kitchen and say, “Yes, I am ready. Show me the treatment of women, show me culture of queer, show me the mothers of the disappeared, show me cyanide gold mines and grandmothers’ resistance, show me trans women called Hande and show the teeth of the police and what they did to her, show me 5000 teenage girls on a Women’s March, kettled in the super highway street of Istiklal, show me that lady in her eighties who sat on a rock with a staff, soldiers in a row behind her, trying to take over the olive grove as she blasts, ‘The State? I am the state here!’’’ You’ll say, “Show me oppression, the politics, police brutality, show me torture, show me 64 guards kicking a dealer to death in the prison at Silivri.” You’ll notice there are less and less women, they’re vanishing at a rate of one to three per day.

There will be an old man to clean your shoes on the pavement before going into court, but because you speak the language and had a family here, you will really talk to him and he will cry tears down a maze of lines from cornflower blue irises, telling you, “Inflation means it’s twenty lira for a few tomatoes, we don’t eat meat and we can’t make a go of it”. You’ll agree it is a sin to take over the Central Bank and to let inflation run at 168%.

By now you will be an international advocate. You will monitor 200 trials, hoping it will all get better. But fascism doesn’t need much sleep. When it’s too late you’ll see that you were not creative enough. You weren’t armed to the porcelained teeth or in league with deep state. How can you succeed? You don’t belong to the right cult. The President will laugh you off: “These people, they come here, make up a few numbers and leave.” At one point you won’t want to believe there are 185 journalists in prison. But you know them, you have met them and hugged them.

In seven years you’ll be scared for twenty minutes. Those twenty minutes on the day you decide to stand up are like being in an iron maiden, seeing your essence squeezed out and poured into a glass phial. You hold it up to the light – it is the right colour. You hand yourself permission to resist. Go and find them. They will show you the meaning of solidarity. They really will. Your dear fierce legal colleague who sticks with you, no matter what. Court reporter girls who stand up to the judge and are the subject of court cases written in the purple official bruise of his ego. The woman with 185 court cases against her, who still sends salvos to officials. The lawyers, physicians. They’re resisting so hard, are we with them?

The first court case you monitor will be Zaman newspaper, the journalist, editor, author and unliked man Ahmet Altan. Why don’t you sit in the front row, a copy of the OSCE Trial Monitoring guidelines on your knee? That’s how you monitor a trial, you see? Are they abiding by procedure? How much spare paper do you have? The trial will begin and you’ll write it all down. Then comes an undercover cop. He’ll lean his whole upper body onto you, staring down at the pad on your lap to read what you’ve written, “Are you with Human Rights Watch?” You should go on to record the rest of the hearing in Welsh shorthand. Barmouth Welsh.

You’ll fly over Mount Ararat, fancy that, with a lawyer called ‘the arrow’. Your combined presence, the lawyer’s arguments will get Berzan out on bail that day. You can change things if you put your energy right into the room. In these times of outsourcing intelligence, of never meeting, of cost-saving, if we stop meeting face to face, stop putting our physical, personal energy in the place where it is needed, where it will be seen and counted, then we will fall down either side of the abyss that is separating us, and will meet in a bloody mess at the bottom, wondering how it happened. The best advocacy strategy meetings will be twelve people around a table in Berlin, or in Brussels, or Istanbul, all equal in struggle and all winning. Slowly some of the elitist ones will unpick themselves like the decoration on a shawl, unwind and leave others in the cold. You’ll work on. Your reports will change the law.

How much is the ticket, you ask. Is it a time machine that will eat tokens made of years, of intimacy, friendships, of all else that exists outside the job? Will it be fuelled by all the poems you wrote and never published? You might only take one day off in seven months in lockdown. What else was there to do but work? When you see how bad it is every moment feels like the threshold of a potential win, of standing with them. And every time you think you’ve made a difference, the state will impress you with their newly proposed law to ban all mention of homosexuality on the internet; their throttling of the airwaves. One small squeeze is all you need once you’ve mastered and collected the horse of freedom, put in the brutal bit of police violence backed up by millions of canisters of poison gas at protests.

You will continue on this journey until the road kinks back and kicks you off the path. You will cling on by your fingernails, while life floats far away. You will stay on the road until a new boss steers the car into the back of a truck marked ‘Investment Bank’ and steals your integrity. Then you will lie about your reasons, out of politeness, and you will leave. You might believe that you can still go on, and that the road will welcome you back, but the road knows you can leave no more tread. That you belong in a field, walking over a bog with a small dog, looking up at the range near where you were born, thinking about sixth century poets, because the remaining road travellers, those local dissenters and human rights defenders, they will go on along the road, two thousand miles away. The fight was always theirs, and they will win. It was never about you.

. . .

Line Stockford is a Welsh poet, editor and translator of Turkish literature. An adviser on Turkey for PEN, she designed and ran human rights projects around linguistic rights and media freedom. She studied the History of Turkish at SOAS, London. Her book-length translations are published by Parthian, Palewell Press and Smokestack Books.