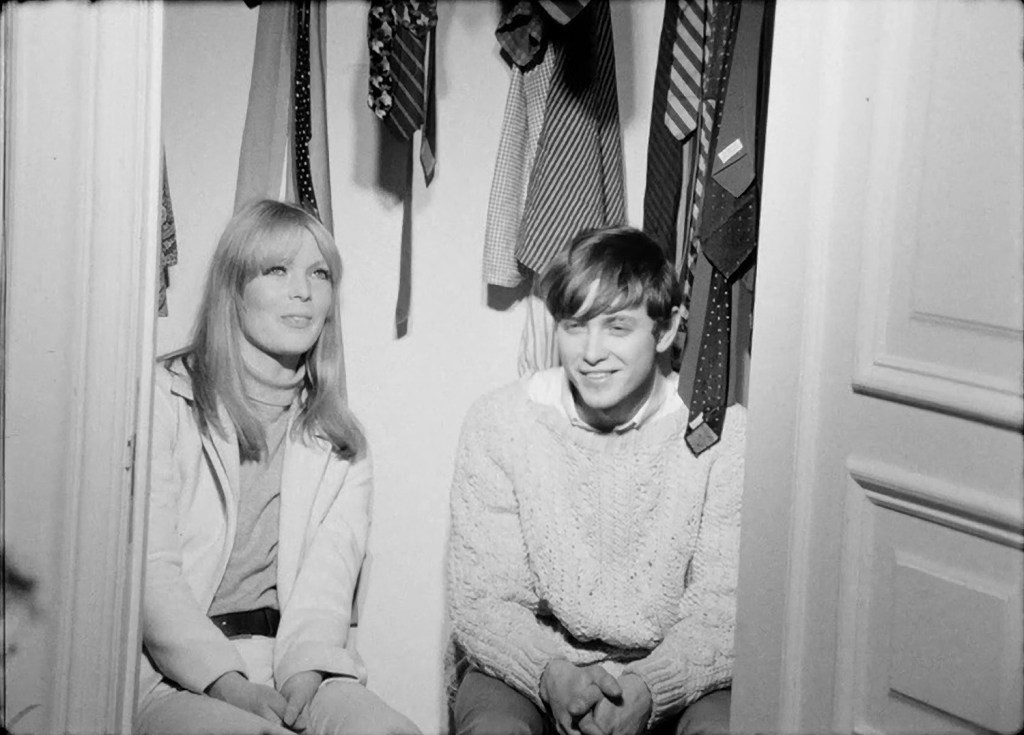

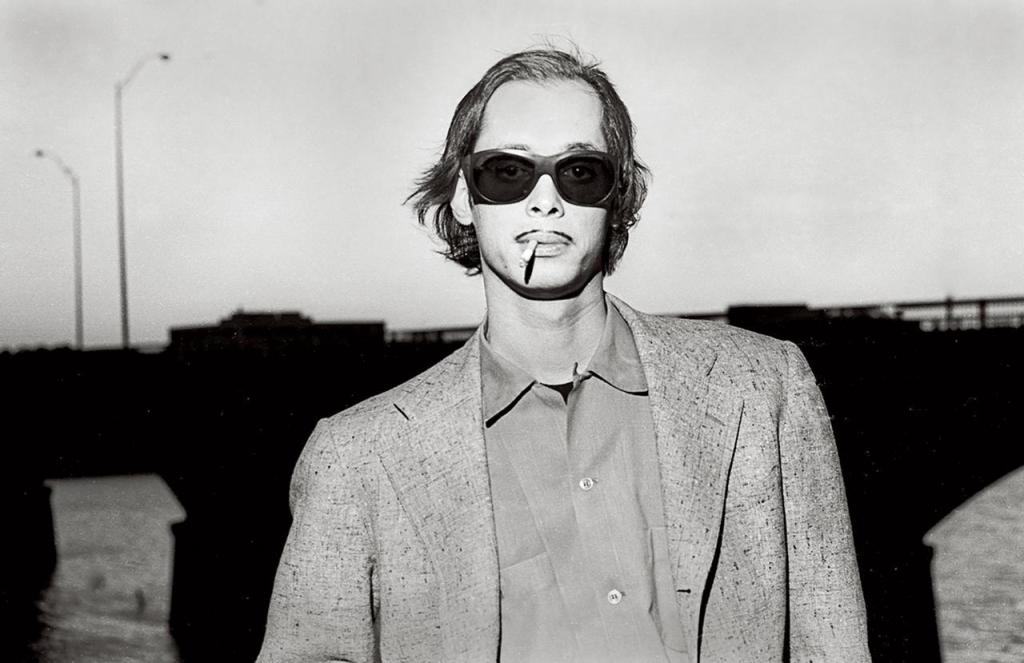

John Waters by Nicolas Russell, Austin, Texas, January 1976.

For so many of us malcontents, the riotous 1981 book Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste by cult filmmaker extraordinaire John Waters represents a sacred text. (I would have first bought it in the late 1980s as a university student, and it’s been a profound cultural touchstone ever since). In the chapter entitled “Sort-of-famous” the peoples’ pervert writes “I know you’re supposed to name-drop in these kinds of books, so here goes: People I Always Wanted to Meet, Did, and Wasn’t Disappointed …” and proceeds to list the likes of Andy Warhol, David Lynch, William S Burroughs and Douglas Sirk. But most tantalizingly for me, he recalls encountering …

“… Nico, my favourite singer, who was so out of it when I met her that she asked, “Have I ever been here before?” (I had to tell her I really had no idea).”

I yearned to know more about this historic meeting between cinema’s Sleaze King and the heroin-ravaged Marlene Dietrich of punk. Flash-forward to December 2010: I interviewed Waters for the sadly long-defunct art and culture magazine Nude in December 2010 when he was in London promoting his book Role Models, so I finally had the opportunity to get him to elaborate on his encounter with Nico.

So here it is: when John Waters Met Nico…

Graham Russell: Tell me about the time you met Nico.

John Waters: Nico … I met her when she played in Baltimore. Well, (before that) I saw her play with The Velvet Underground at The Dom on St Marks Place (in New York) with The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. I have the poster still. But I met her much later when she had her solo career, which I loved. She was a total heroin addict. Did you ever read that book The End? (The 1992 book is a jaundiced and not exactly objective account by her former keyboardist James Young). It’s so hilarious. It was that – although it wasn’t that, that was later when she was touring England. She played at this disco, and I went. And people went, but not a lot, it wasn’t full. And she was heavy and dressed all in black with reddish dark hair, and she did her (he makes guttural moaning noise). Afterwards I said, “It’s nice to meet you, I wish you’d play at my funeral”, and she said (mimics doom-laden Germanic voice), “When are you going to die?” I told her, “You should have played at The Peoples Temple; you would’ve been great when everyone was killing themselves!” Then she said, “Where can I get some heroin?” I said, “I don’t know.” I don’t take heroin, so I don’t know. But even if I did, I wasn’t copping for Nico!

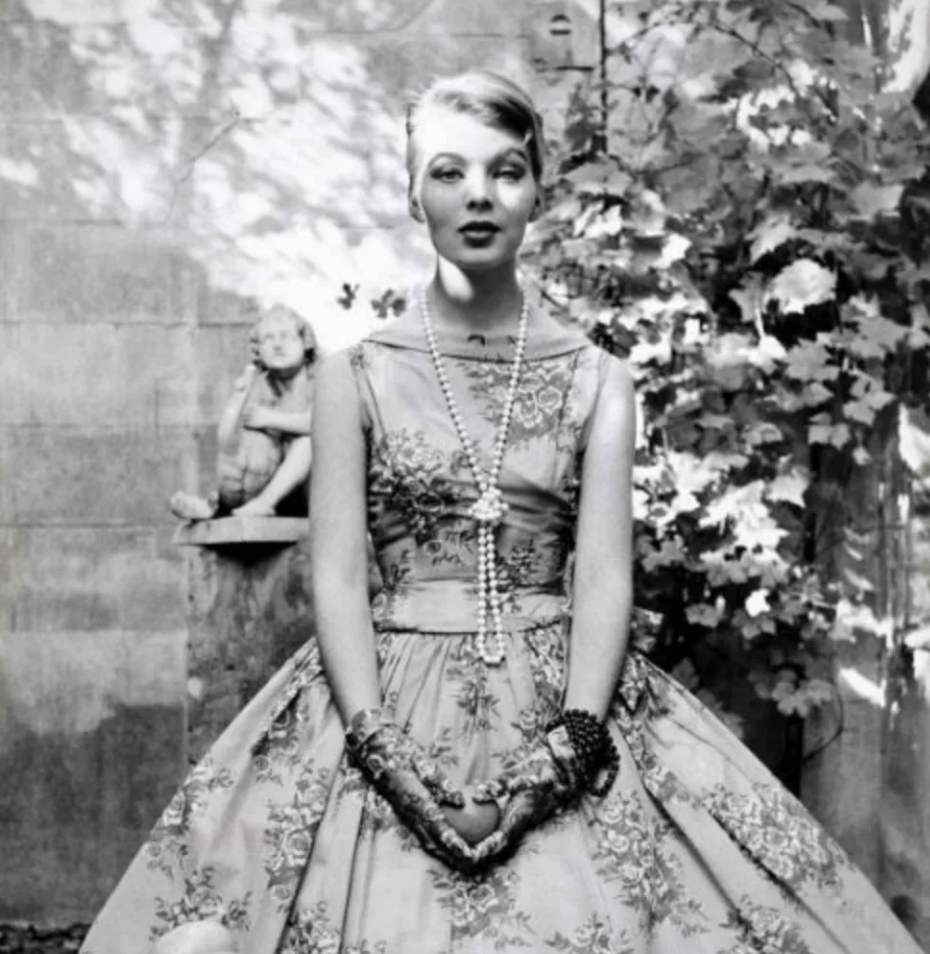

“But that was basically it. But I’ll always remember her, and I love Nico. I remember when she died, when she fell off the bicycle (in 1988). Every summer my friend Dennis and I, we play Nico music on the day she died (18 July). I saw that documentary Nico-Icon (Susanne Ofteringer, 1995), which was great. It’s a shame: she was mad about being pretty! She was sick of being pretty, being a model. And I remember her when she was in La Dolce Vita (1960), even before. Nico … great singer; and even The Velvet Underground hated having her. And her music can really get on your nerves. You have to be in the mood. Sometimes it gets on my nerves. You have to be in the mood to listen to it. To put on a whole day of Nico can be … my favourite song of Nico ever, and I only have it on a tape that someone made, it’s a bootleg. Did you ever hear her sing “New York, New York”? It’s great! I wish she’d done a whole album of show tunes! Like “Hello Dolly” or “The Sound of Music”! (Mimics Nico singing “Hello Dolly”).

Like the Shangri-Las song, Graham Russell is good-bad, but not evil. He’s a trash culture obsessive, occasional DJ (Cockabilly – London’s first and to date, only gay rockabilly night), and promoter of the Lobotomy Room film club (devoted to Bad Movies for Bad People) at Fontaine’s bar in Dalston. As a sporadic freelance journalist, over the years he’s contributed to everything from punk zines (MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, Flipside, Razorcake) to The Guardian and Interview magazine and interviewed the likes of John Waters, Marianne Faithfull, Poison Ivy Rorschach, Lydia Lunch, Henry Rollins and Jayne County.