Continue reading “Two micros by Stevie Aechelimi Spikes”biting the inside of my mouth i am more gum than smile, because even on the internet i don’t know how to say no in the breathless space of a text message

Continue reading “Prism 1 & 2 by Kenneth M Cale”ciphers small

upon a plinth

Continue reading “Excerpt from The Book of Khalid by Ameen Rihani”… the Soul of a philosopher, poet and criminal. I am all three, I swear…

Continue reading “transmogrification by Sara Campos-Silvius”I will be something utterly, gloriously new…

Continue reading “Excerpt from Christ by Sadakichi Hartmann”Thought and feeling are forgotten, only the body lives!

Continue reading “Holy Water (Overflow) by Colin Campbell Robinson and Paul Hawkins”We slip out into the night-bar, drink beyond satiety; fall in the

street of inequality, the place we live.

Continue reading “At the Carnival by Anne Spencer”For you—who amid the malodorous

Mechanics of this unlovely thing,

Are darling of spirit and form.

Continue reading “Crown of Thorns by Alice M.”… when she kneeled at the altar, we saw blood fall, not blood I whispered not blood at all, but purple blackberries, bouncing fat on the stone

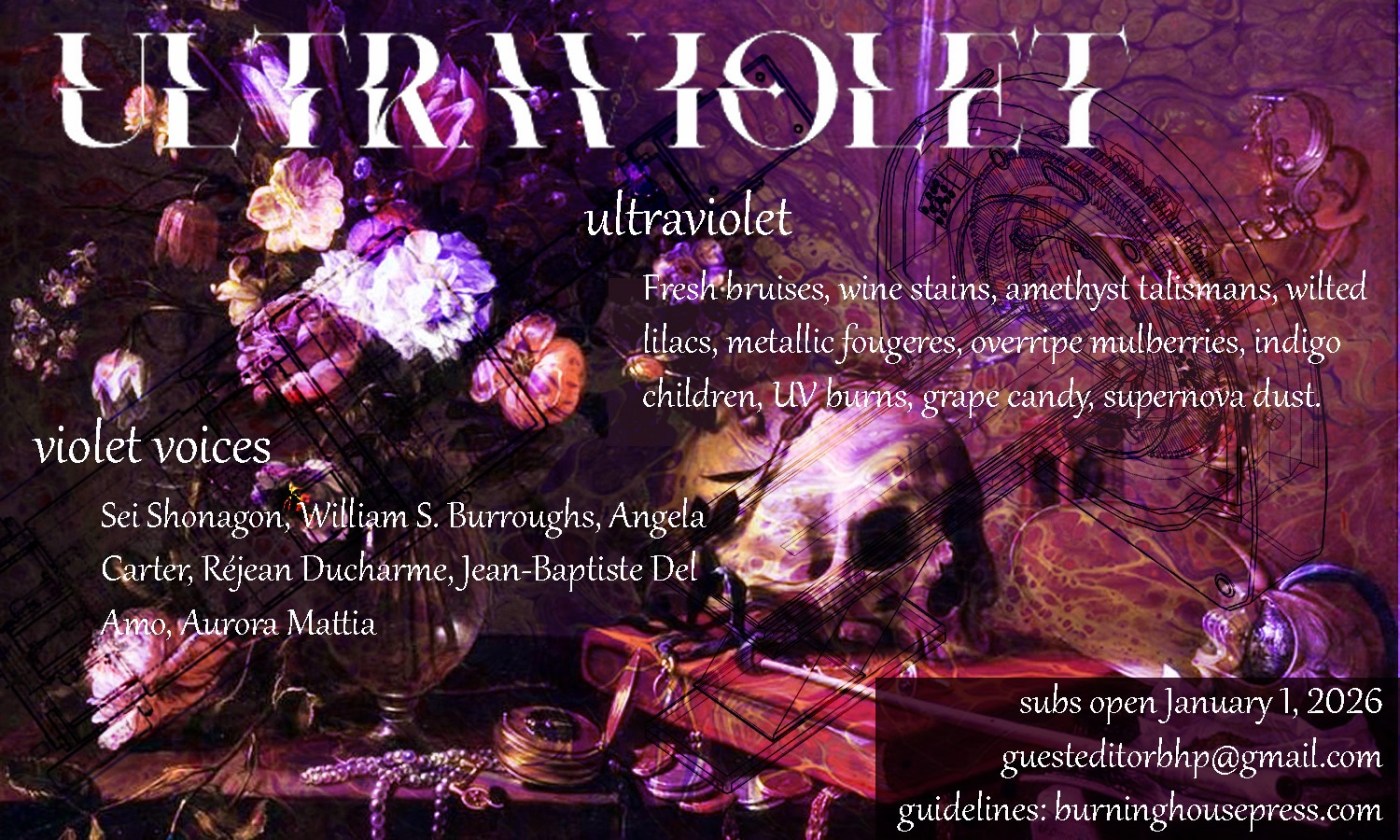

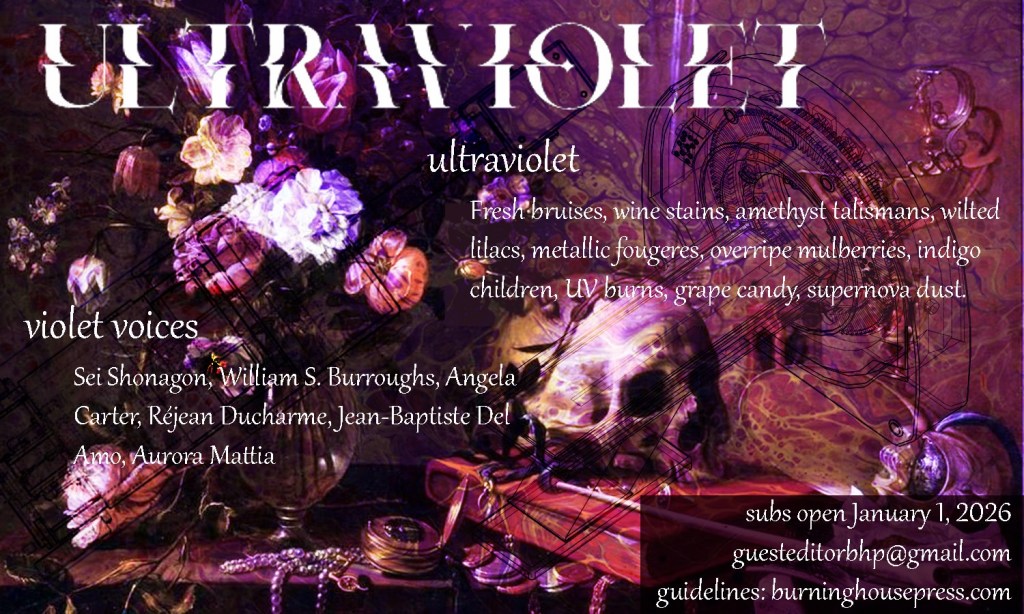

I’d intended to write a brief introduction to the ULTRAVIOLET themed issue of Burning House Press but will instead juxtapose two seemingly incongruous observations.

Continue reading “ULTRAVIOLET: Guest Editor’s note”Burning House Press are excited to welcome Kawai Shen as the sixth BHP guest editor of our return series of special editions! As of today Kawai will take over editorship of Burning House Press online for the month of January.

Submissions are open from today 3rd January – and will remain open until 25th January.

Kawai’s theme for the month is as follows

___

ULTRAVIOLET

- Fresh bruises, wine stains, amethyst talismans, wilted lilacs, metallic fougeres, overripe mulberries, indigo children, laser burns, grape candy, supernova dust

- Inspiration: Sei Shonagon, William S. Burroughs, Angela Carter, Mervyn Peake, Réjean Ducharme, Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, Aurora Mattia

Kawai Shen is based in Canada. Her fiction was shortlisted for the 6th edition of The Metatron Prize for Rising Authors and was selected for the Best Canadian Stories 2025 anthology. She has published work in khōréō, ergot, Extra Extra, The Whitney Review, A Fucking Magazine, and more. Her book, Wavering Futures, is forthcoming with Metatron Press in 2026.

______

- SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

- All submissions should be sent as .doc or .docx attachments to guesteditorbhp@gmail.com. No cover letter is necessary but please include a short third-person bio and (optional) photo of yourself for potential print with your submission. You may also consider including social media usernames, especially if you’re on Bluesky/Instagram– I want to promote your work!

- Please state the theme and form of your submission in the subject of the email. For example: ULTRAVIOLET/FICTION

- Submissions are open until 25th January and will reopen again on 1st February 2026 for a new theme/new editor/s.

- Fiction: Fiction should be limited to 1,500 words or (preferably) less. Up to two micros (maximum 500 words) may be sent.

- Poetry: You can try your luck with poetry, but this issue will focus on purple prose. Submit no more than three poems.

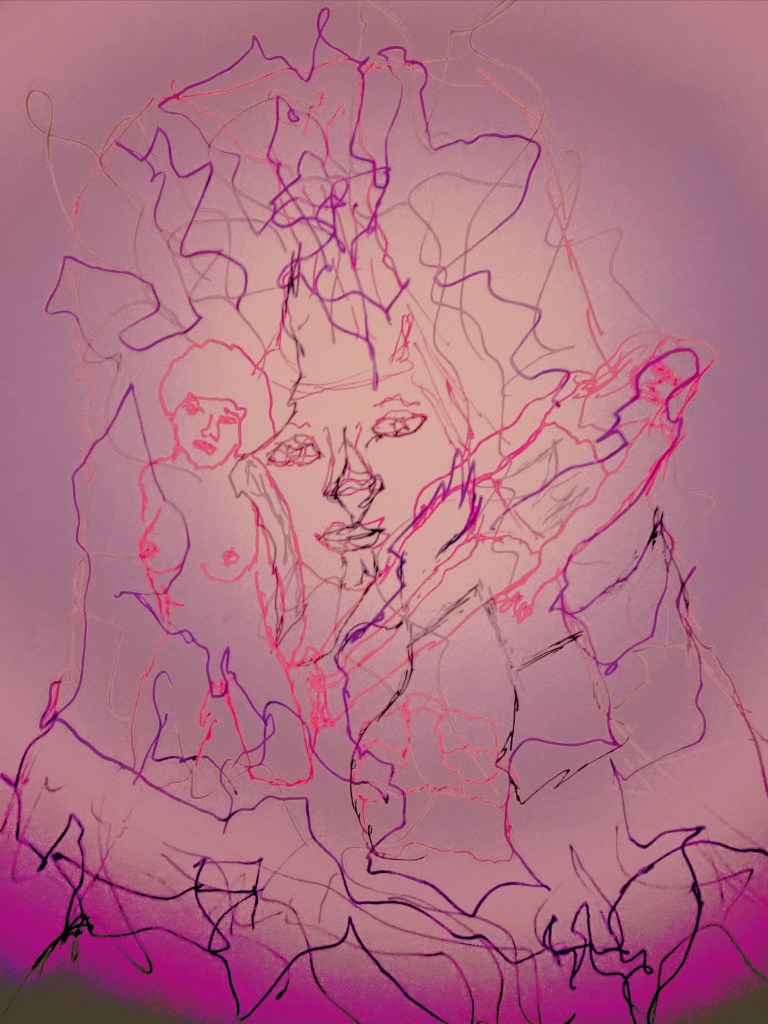

- Art: Submit a maximum of six hi-res images of your work in JPEG format (maximum size 2MB) with descriptions of each work (Title, Year, Medium) in the body of the email. File names should correspond with the work titles.

_______

BHP online is now in the capable hands of the amazing Kawai Shen – friends, arsonistas, send our January 2026 guest editor your magic!

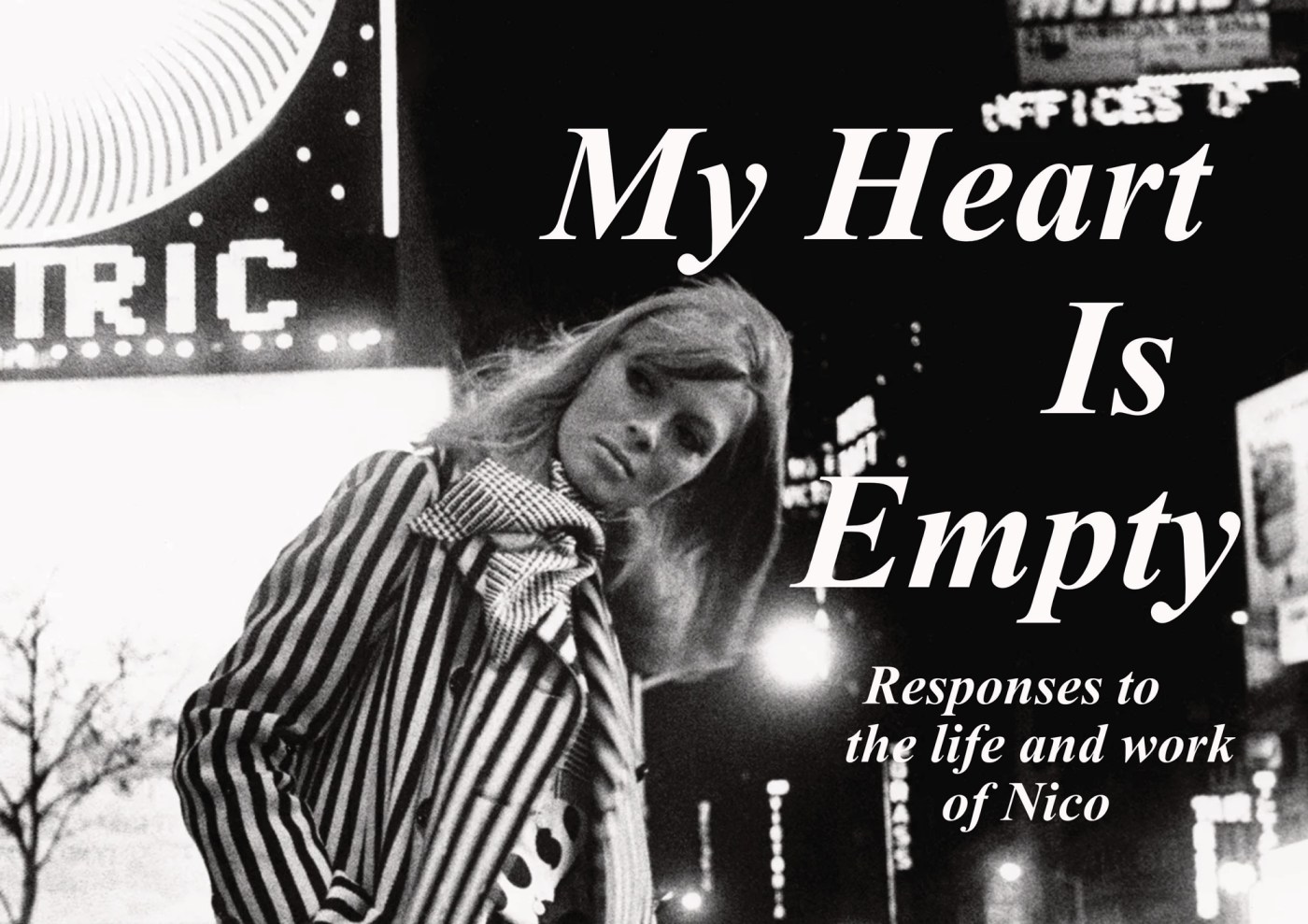

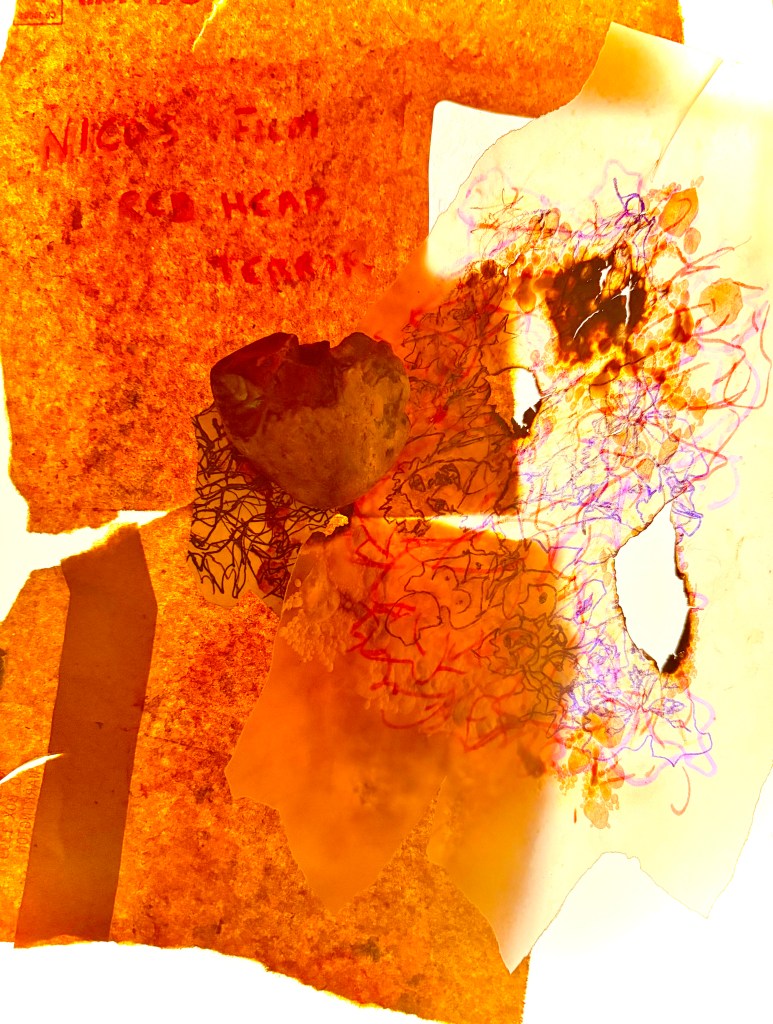

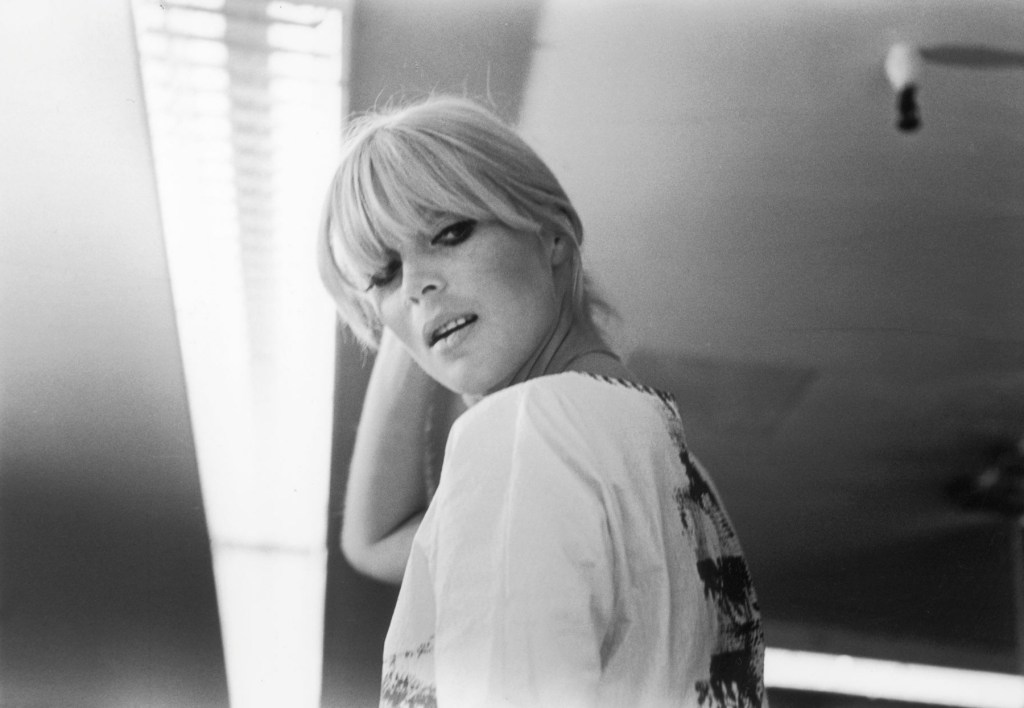

From Nico Femme Fatale compilation.

At the age of twenty-four, I decided to die. I planned it all out like a game. It was like ordering a shiny dress from a catalogue. Twenty-four was the perfect age to die.

This boy lived under a low star. Sickly spell of youth. He was hypnotised by the fragile beauty of the world. A river shining in autumn in Lancashire woods. His heart was like a castle of vanity. He wondered if people threw themselves off motorway bridges because they understood freedom like no one else.

I didn’t want to speak about myself so I wrote a story. I didn’t want to hear myself think so I sang a lonely song. Nico once said, “You don’t have to be you to be you. I see that now. All the deaths contained inside, rich and plentiful as golden black.”

You don’t have to be you to be you.

Nico by Steve Katz.

The boy, who had planned death out like a game of hopscotch, worked in an office. He wrote copy for companies about everyday objects. He spent an entire week writing about synthetic rubber tyres. Language was nothing but the accomplice of death and money. He looked outside. On the opposite side of the road was a rendering plant. They fed the carcasses of animals into enormous steel drums and boiled them into soap. When the smell began to belch into the air from endless chimneys, the workers closed the office windows. But the smell always got in and they were always complicit.

I believed I had figured out life as a magic trick. It was like when you smoke too much weed and you have the cheapest of epiphanies. It comes at you like a cartoon eureka moment. But soon, it floats away because every revelation in human history is simply a balloon in the big blue sky. I laughed. I took ecstasy pills with a beautiful friend that changed sex. We laughed harder until I threw up into the grass.

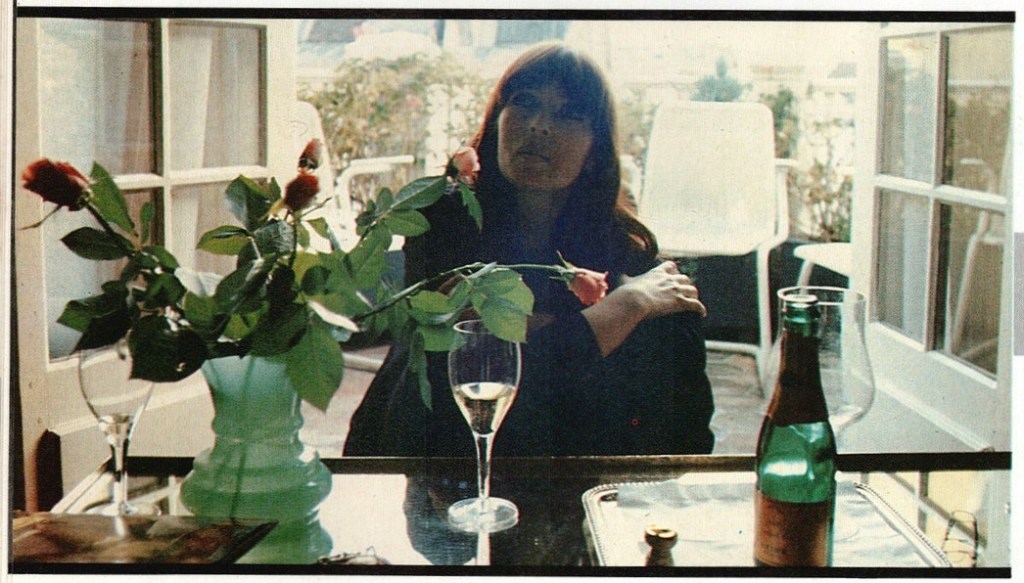

Nico in NME magazine, 1974.

Every day, the boy would walk from the office along a canal where Victorian mills rotted into dark water. Nico was a huge fan of the Situationists. Raoul Vaneigem once wrote, “Who wants a world in which the guarantee that we shall not die of starvation entails the risk of dying of boredom?” The boy wandered past enormous cocks graffitied across the stone walls, phone numbers to unknown men in unknown towns.

I never bought albums from the dead because I had the internet by this point. There seemed no reason to line the pockets of parasitic men. I was a parasite too. Endless nights downloading poets through progress bars. Low-quality mp3s like green waxing moons. The next one on the list: Nico_The_Marble_Index. The internet was a vast séance. Nico once said, “When I sing I try to imagine I’m all alone, there’s nobody out there listening.”

Across from behind my window screen

Demon is dancing down the scene

In a crucial parody

Demon is dancing down the scene

The boy was alone. He walked through barren woods in Oswaldtwistle during winter. The saplings were covered in litter. A no-man’s land of polystyrene takeaway boxes and rainbow foil. He formed a paradise inside his own mind. He was like a demon risen from the frozen earth. His grave was covered in soiled condoms and torn-up newspaper. He watched videos on his laptop of Nico playing in a warehouse in Preston in 1982, about sixteen miles west of his current location, and backwards another thirty years. Time and space came apart inside the hand of the demon. She looked bloated on the screen with heroin and fag ash. No one is there.

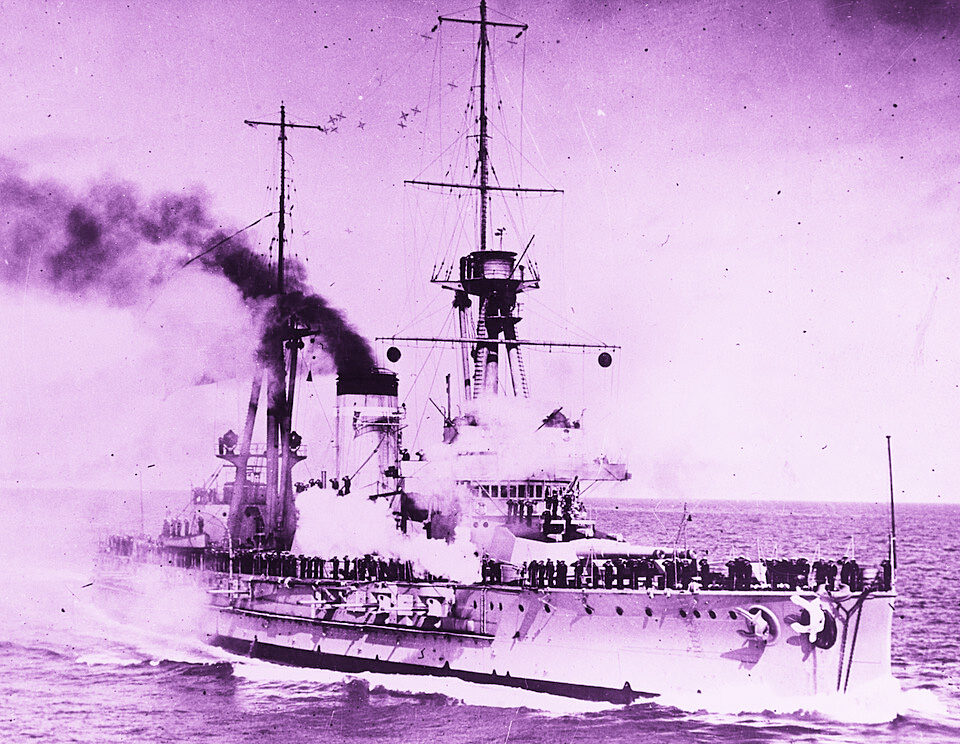

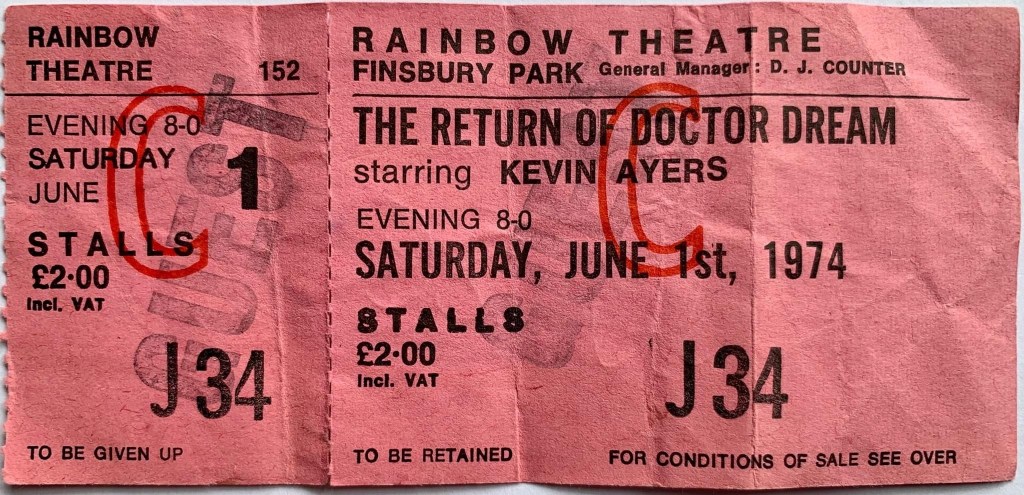

Kevin Ayers, John Cale, Nico and Brian Eno live at the Rainbow Theatre, Finsbury Park, London, June 1, 1974.

I wondered who Nico met in the Californian desert, her body unravelling from peyote like a chain of orange sickle moons. Or when she sang alone to her own shadow in a Manchester terraced house; light starting to appear between curtains as dawn stormed the crumbling walls. An emerald packet of Rizlas. A bottle of vodka shining on the windowsill. Someone’s hand turns a tarot card over on the kitchen table. The Chariot. A king holding a red glowing orb. Nico once said, “A poet sees visions and records them.” I imagined that Nico met a version of herself in the desert. She took off her clothes and led in the dust with this other version of Nico. She kissed her on the lips. And then slowly, beneath the opulent sun shining like a black flower of death, the other Nico whispered a number of secrets into her (the original Nico’s) ear. When Orpheus returned from the Underworld, he was covered in bright red earth.

A true story wants to be mine

A true story wants to be mine

The story is telling a true lie

The story is telling a true lie

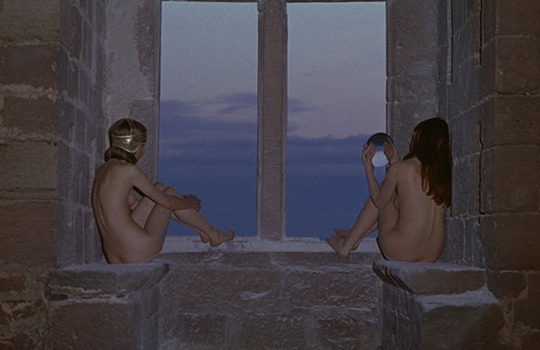

Athanor (1972) still.

The day came when the boy had planned to die. It was a dull day, just like any other. Cars streamed beneath his window. But the day simply passed him by. He wasn’t sure why. He was like a cloud or a ghost that didn’t matter. In a 1997 interview, when asked about the initially low sales figures for The Marble Index, John Cale replied, “You can’t sell suicide.”

The boy wrote down a story that was a true lie. He searched YouTube for all the comments that others had left about a dead singer and stitched them together. He stayed on stage a few moments longer as the audience grew restless. They looked at their watches and coughed and rolled their eyes. Beneath an artificial light, he approached the microphone and read a poem for Nico.

an electric blue current

a leopard in the air

an android serving macrobiotic rice

with tabasco sauce

who forgot to pay the light bill

and lived happily in the dark for a month

Ari watching his mother

putting makeup on in the mirror

illusions of our images becoming permanent

a son growing into an emperor

in a scarlet tunic

rising through a worm hole

red chariot across night sky

love is like a big cloud

a prayer or a song

raining down on you

in the middle of an apocalyptic movie

before the solar flare footage

in the forest above the water

where her grave lies

painted in crystal

she woke up at the end of time

smoked some grass

and went for a ride on her bicycle

an electric blue current

a leopard in the air

Matthew Kinlin lives and writes in Glasgow. His published works include Teenage Hallucination (Orbis Tertius Press, 2021); Curse Red, Curse Blue, Curse Green (Sweat Drenched Press, 2021); The Glass Abattoir (D.F.L. Lit, 2023); Songs of Xanthina (Broken Sleep Books, 2023); Psycho Viridian (Broken Sleep Books, 2024) and So Tender a Killer (Filthy Loot, 2025). Instagram: @obscene_mirror.

Tom Bland has two books out, Camp Fear and The Death of a Clown, with Bad Betty Press. He trained in experimental theatre and found a way to work with poems in unusual somewhat dangerous magickal rituals, and he always performs with Steve-O in mind.

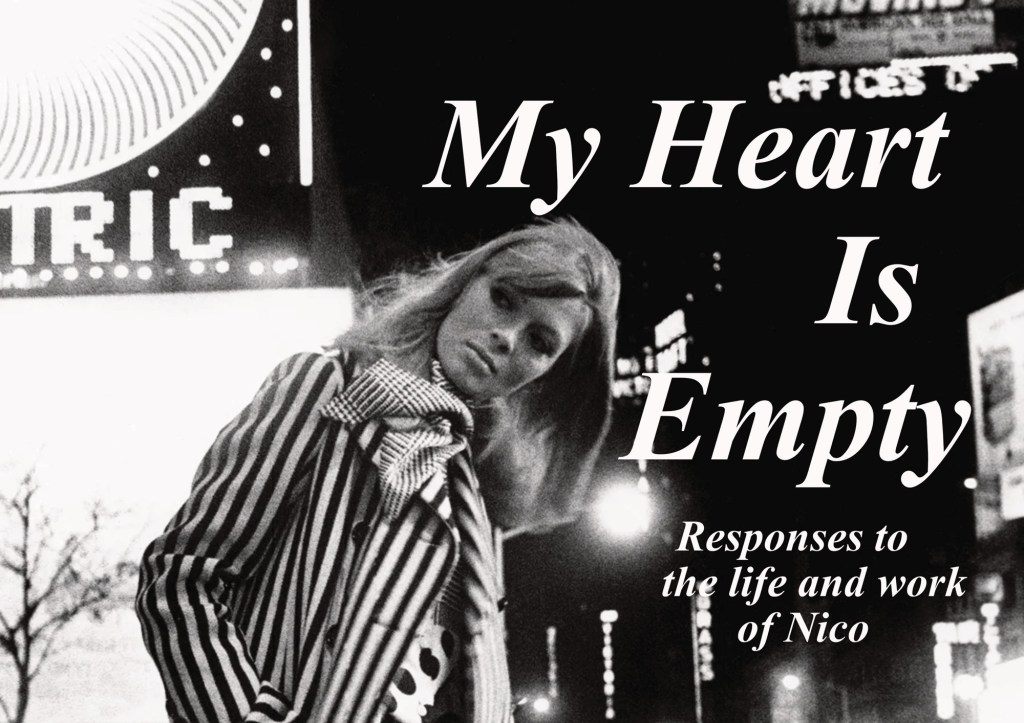

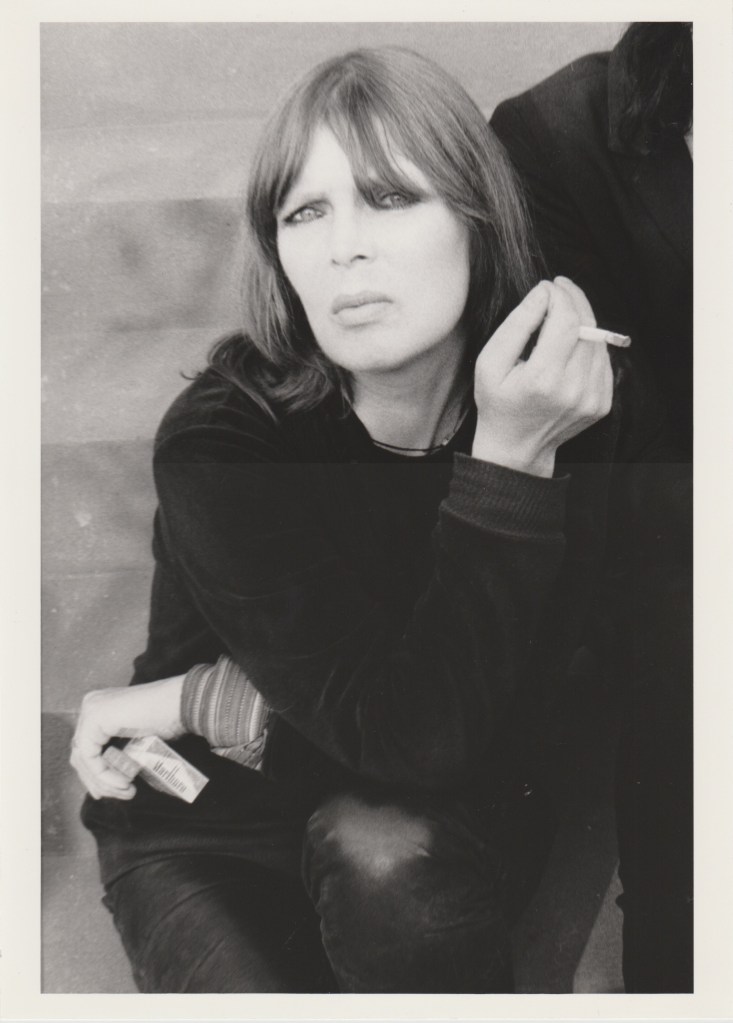

Nico in department store, New York, November 9, 1966. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah.

Sean G. Meggeson is a poet and video artist, living in Toronto, Canada where he works in as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist with his dog, Tao. He has been published in Antiphony, bethh, Die Leere Mitte, Ice Floe, Version9Magazine and others. He won the League of Canadian Poet’s Spoken Word Award in 2024. Meggeson has published three chapbooks, Cosmic Crasher (Buttonhook, 2024), ta o/j , and soma synthesis (both from lippykookpoetry, 2025). Forthcoming: a full-length poetry collection, j: poems (primitive press, Toronto, 2026). Video poems forthcoming in IceFloe, and Infocalypse Press.

Nico, Kensington Gardens, London, March 1970 by Barry Plummer.

Your eyes will show me where to cut.

My father twice allowed himself to be with a woman. The first, when he spent frivolous summers flip-flopping around Europe, was the famous German model and signer so instantly charmed by his boyish loveliness, she knew she’d devour him that night. They met at a summer party in Paris; she willed herself onto him, cozied up beside him, pinned him, sitting inches taller than him, wrapped her long arm about his, black widow silk coiled around a termite. They all saw it, the troupe, her hunger for him. Despite his saying “I don’t know how to do it with a girl! What am I gonna do?” she could not be stopped. Nico took what she wanted. My father couldn’t resist. She liked men of all kinds. Tough guys, artists, fashionistas, princesses like dad.

It’s a lifelong pursuit to seize the look. I freeze the frame just at the exact moment, so your eyes can show me.

The second woman was my mother. Ten years later. Spitting image of Nico, but shorter. Same eyes. Same cheeks. Father saw the thing he saw a decade before. They met on an empty train to New York. She got on after him and chose to sit right beside him. Beside him she transmuted his nerves into embers; her eyes sucked a part of him out permanently. My mother had the same tormenting eyes as Nico. Nearly the same ghostly voice. So my father told me. They were married for three months, until he forgot how to love this imitation. She wasn’t the real thing. He had lovers more his speed to return to. A year later she tracked him down by train, with me in a baby-vomit-stained blanket. Materialized right at his door, handed me to him, and was gone.

If I freeze the frame in the right fragment, I can see you looking into the camera, as you walk.

5-year-old me asks, “When will I meet mommy?” He sneers and rolls the film from La Dolce Vita. That first moment she steps on screen, when Mastroianni calls to her like he would a prowling cat. His face lights up under the shades. There, she is born. I look at father, his face lit up exactly the same as dashing Marcellino.

I rewind the VHS one and half seconds and press play, and then pause. I’ve missed it. I try again.

Nico said of Bob Dylan “He should not wear sunglasses. His whole personality is in the eyes.” My surrogate mother had the same thing. She was speaking of herself. I stop the tape again. I see in these eyes scorched desire. Preordained junky eyes. A life once lost. A yearning that could find no earthly release.

Father catches me cumming to this frame, sitting on my carpet floor, the VHS paused, the streak of semi diagonal static slicing through the black and white, my surrogate mother’s eyes almost, almost, locked on mine. He doesn’t say anything. He closes the door.

My father tells me that Nico used to sleep with Brian Jones, and that he would abuse her in the bedroom. Beat her, stick pins and needles in her. He we cause her all kinds of traumas, his consciousness bombarded by nonstop cocktails of drugs. But still, it was him that was afraid of her. Short little man like all the Stones, she a tower beside him. When he was sober, or close to it, he was her best lover she ever had. Years later I will ask myself how my father knows these details, and why on earth he thought to tell me. And I will remember. He was obsessed, until his death.

If I were my father, I would want to ask me, why this frozen frame? Why is this the image I choose? If I flip through his shrine of magazines, his amassed clippings, there’s dozens of full color pictures of her. And I wouldn’t tell him anything.

Father has a date with a short man with fading blonde hair. The man is German. I hear them laughing together in the living room. I hear the clinking of their glasses as they cheers over and over. I sit above them in my bedroom, pretending to be asleep. I rewind the tape.

Nico’s face looks down. She looks forward and off to the crowd. I try to make her eyes see mine. I never met my mother. Father said she died in a train derailment last year. Father has pointed to this black and white screen and said this is your mother, on drunker nights when I try to ask him again about her.

I flip through all the magazines. I slowly cut pages out over time. I use a boxcutter because my idiot father has that, but no scissors. A page here, a page there. Father would kill me. Her face desecrated. I stash them under my bed. I glue them together in parts. The scene on the TV is frozen in time. She watches as I work. Her eyes are just right. My floor is covered in glue. My surrogate mother’s face breathes beneath my bed, in multiples, in endless variations of cascading light and dark. I feel her lungs at night. I breathe her into me.

Derek Fisher is a writer from Toronto. He is the author of Container (With an X Books, 2024), and Night Life (Posthuman Magazine, 2023). He has work published in Maudlin House, X-R-A-Y, Wigleaf, The Harvard Advocate, Fugitives & Futurists, SARKA, Vlad Mag, and more. To see more of his writing, visit derekafisher.com

Nico & Lou Reed , 1975.

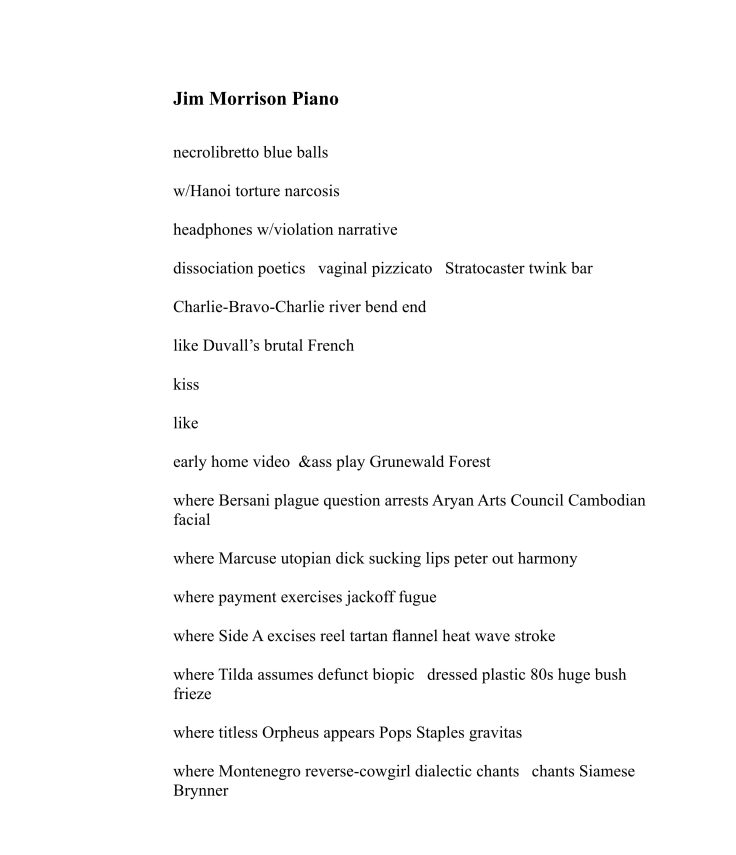

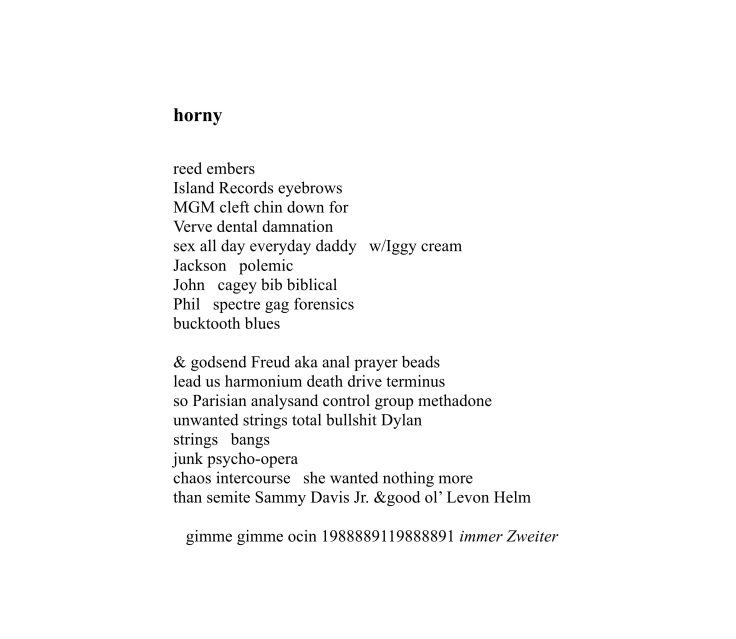

Damon Hubbs is a poet and editor from New England. His collections and chapbooks include: Venus at the Arms Fair (Alien Buddha Press, 2024), Charm of Difference (Back Room Poetry, 2024) and Coin Doors & Empires (Alien Buddha Press, 2023). Recent publications include Expat Press, Apocalypse Confidential, BRUISER, Horror Sleaze Trash, The Literary Underground, & others. His latest collection, Bullet Pudding, is forthcoming from Roadside Press in 2026. His poems have been nominated for the Pushcart and Best of the Net.

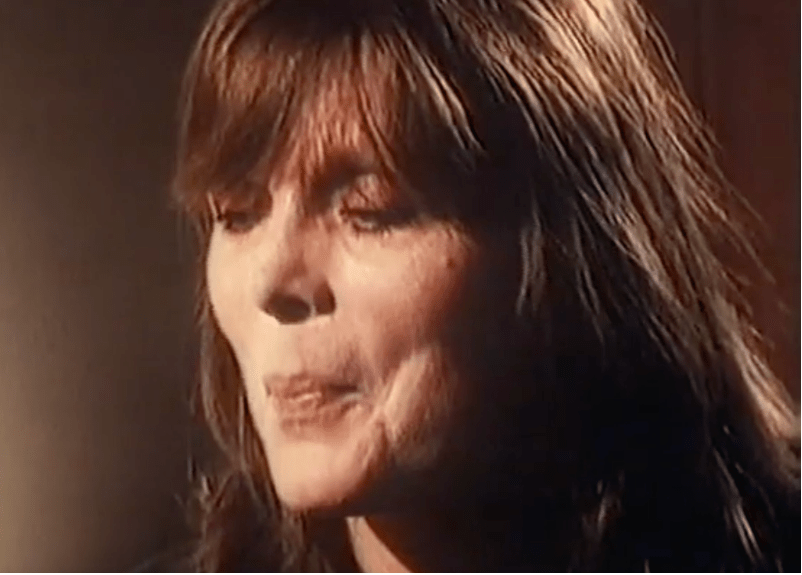

An interview from 1985, in Belgium, before or after a show where she performed My Funny Valentine with a drink in her hand, swaying and looking up into the lights.

The lines around her eyes and her easy smile. The lines around her mouth and her serious eyes. Her browned teeth.

It feels like every beautiful woman I know, whether in her twenties or her fifties, has recently tried to engage me in the talk about botox and fillers and surgery.

I don’t know what other women want from life, or why so many of us can be so easily fooled into hating time or pretending it away, but I end up saying the same thing over and over again, no matter where the talk goes:

I just can’t do it and there is really only one reason why:

I have never, ever, ever—never even once—looked at another woman and thought “she’d be beautiful if only she had no wrinkles, she’d be beautiful if only her eyes weren’t hooded, she’d be beautiful if only her acne scars were erased, she’d be beautiful if only her flesh were stretched tighter around her bones.”

And if I don’t trust my aesthetic intuition, what kind of an artist am I? If I let them convince me that someone other than me decides what I find beautiful, why bother ever writing another word again?

I know this is why artists are monsters. It’s why I have always been a little afraid of myself. But our lives are our works of art. We will eventually arrive at the moment when we can no longer deny it. For most it’s on the deathbed.

Just watch Nico talking and singing in 1985.

The 70s were a broken bridge, she says. She’s not excited by the fact that every band since the late 70s has listed The Velvet Underground as a significant influence. Why not? asks the interviewer. Because it gives me the feeling that I’m stuck in the 60s, she says. And the 60s and the 80s are too much alike already, she says. But why? asks the interviewer again. It’s the same paranoia, the same fear, she says. But the 70s were really different, she says. And they were a broken bridge. World-weariness overtakes her face, sorrow glimmers at the edge of her eyes.

She is otherworldly calm as she answers questions, as though she’s somehow had a long time to search her life and arrive at her responses, but this is no rehearsed interview. She can stop time with her presence, and so she doesn’t need to pretend that she’s not in time—aging—with her face or the rest of her body.

This interview has unnerved me. It’s what I can and cannot see in her eyes.

I’ve thought about it for days, feeling something emerge within and around me. Something distinct and real, like its own entity. I’ve let it exist as a kind of haze around me, until this morning, when it took shape. It’s this:

if there’s one thing I can do for my daughter (by which I mean all of life, the ‘future’ itself, the potential continuation of humanity) it’s that I can show her (us), with my life, that time is not to be feared. That life is not to be feared. That sorrow and joy are not to be feared. That moving through this mysterious game in which laws of time and gravity and space contain us is a wonder to behold. And to play. Simultaneously. In it and unafraid to also be of it.

A friend asked me, But what about her cruelty? The terrible things she might have said?

I don’t know why, or if, Nico has said the hateful things some say she said, but I know that we all know hatred in our own very personal ways, and we’ve all seen what it’s like when hatred has too firm a grip on someone who has usually been able to keep it in check. This is perhaps the lesson of now. Moving through time is not easy. It excuses nothing, but it’s true. This fact is on our faces and in our eyes and our necks and backs and hands and hips. And in every word we utter.

Maybe today I’ll visit her grave in the forest.

Lindsay Lerman is the author of two books, I’m From Nowhere (2020) and What Are You (2022). She is the translator of François Laruelle’s first book, Phenomenon and Difference. Her short stories, essays, and interviews have been published in The Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Tyrant, Archway Editions, The Creative Independent, and elsewhere. She has a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. She lives in Berlin.

Nico, Beggars Banquet Records.

Jessie Lynn McMains (they/she) is a cross-genre writer, visual artist, and longtime zine-maker currently living in the woods in northeast Wisconsin. They were the 2015-17 Poet Laureate of Racine, WI, and one of their poems received an Editor’s Choice commendation in the 2023 Allen Ginsberg Poetry Awards. They are the author of numerous books and chapbooks, most recently There Will Be Singing About the Dark Times, a hybrid audio/print chapbook, which you can find more about on their website recklesschants.net.