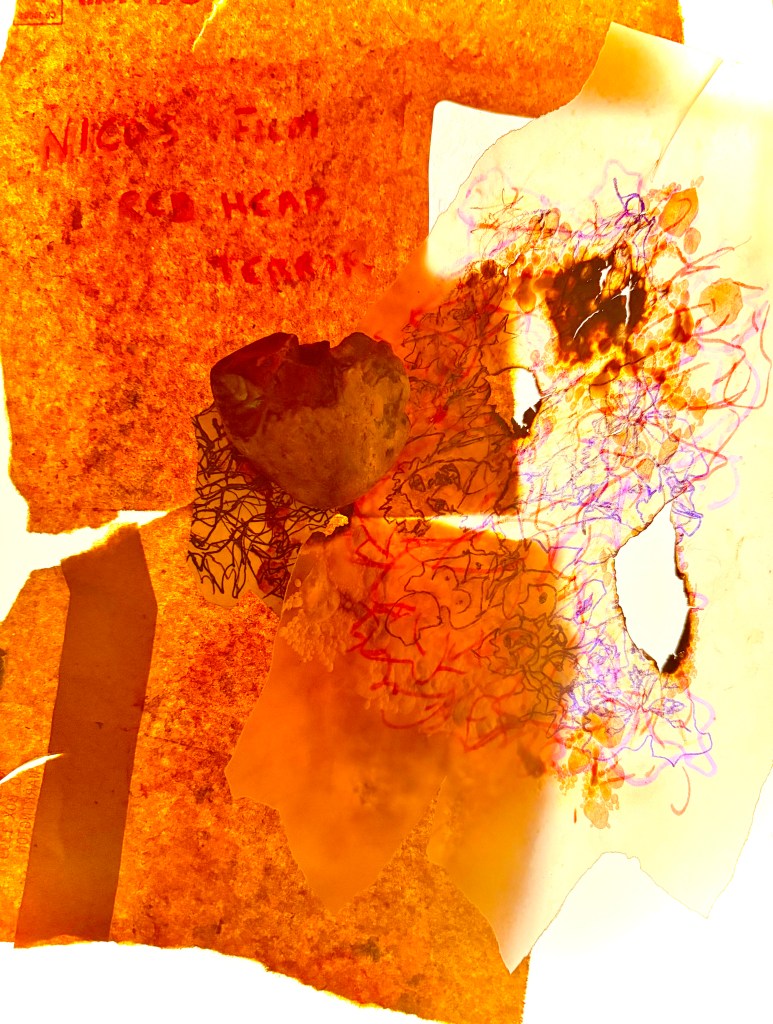

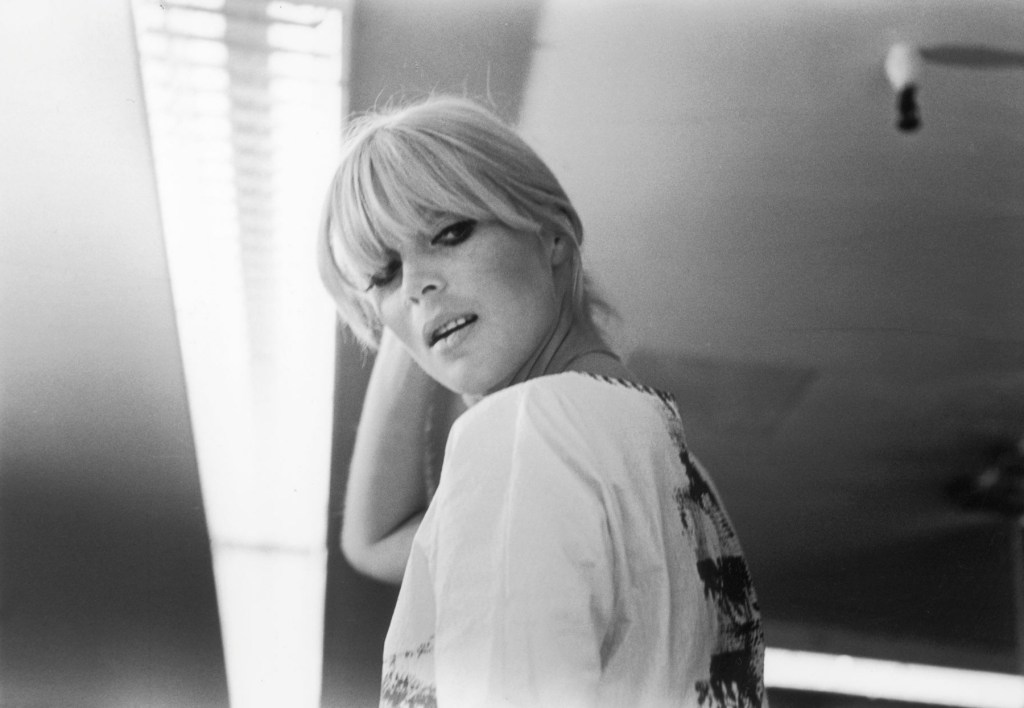

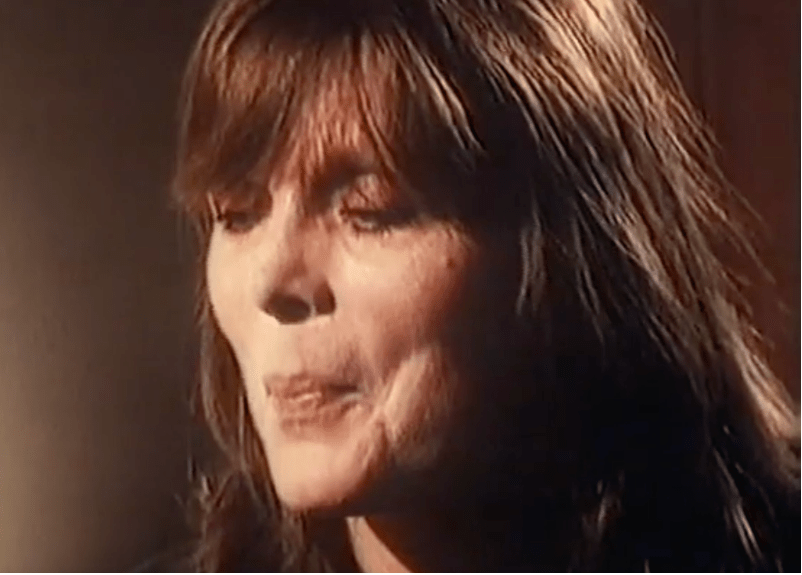

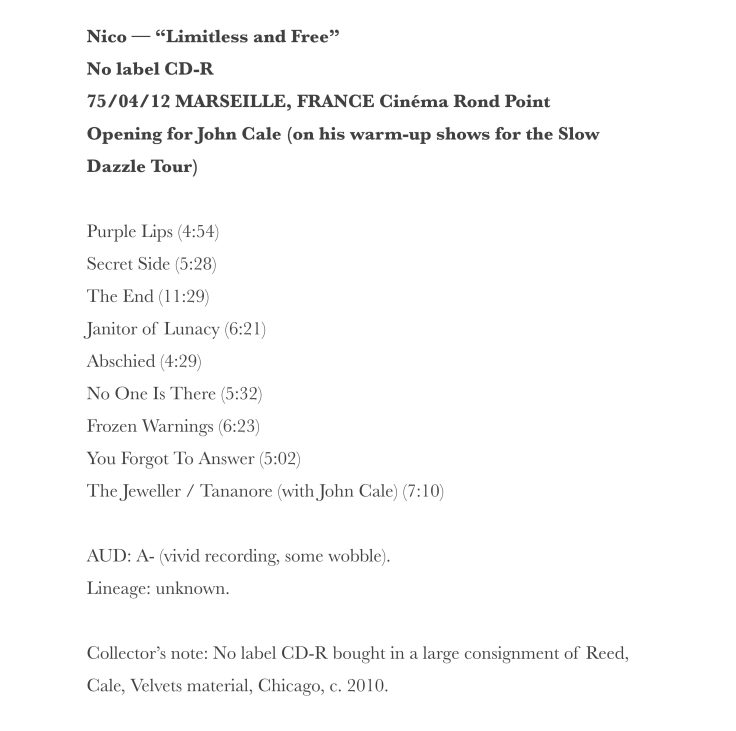

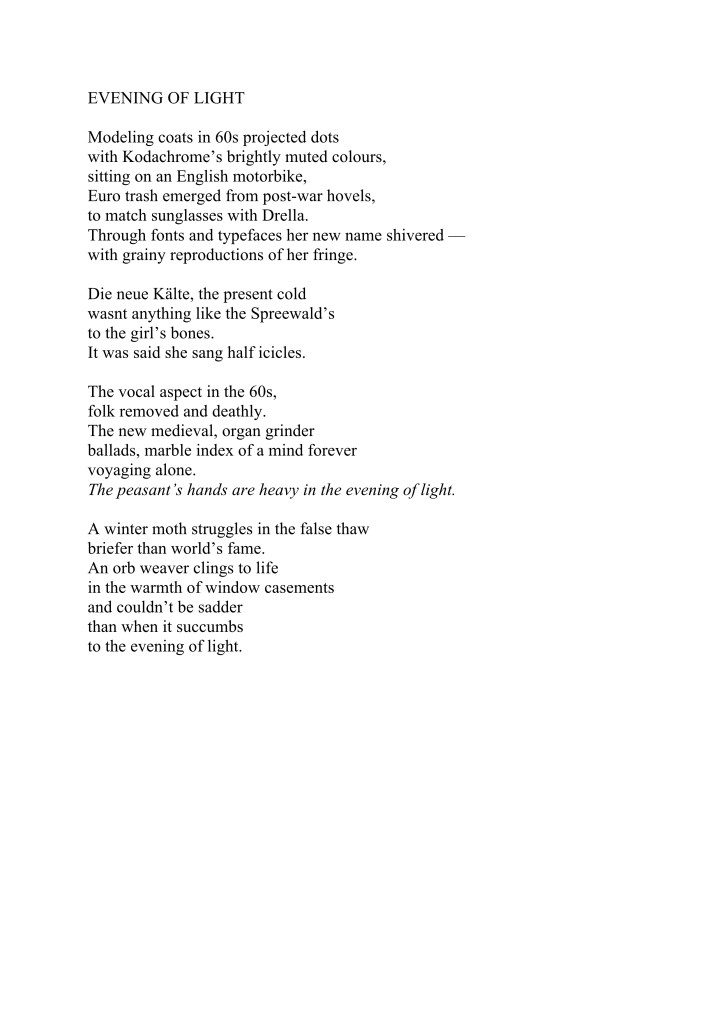

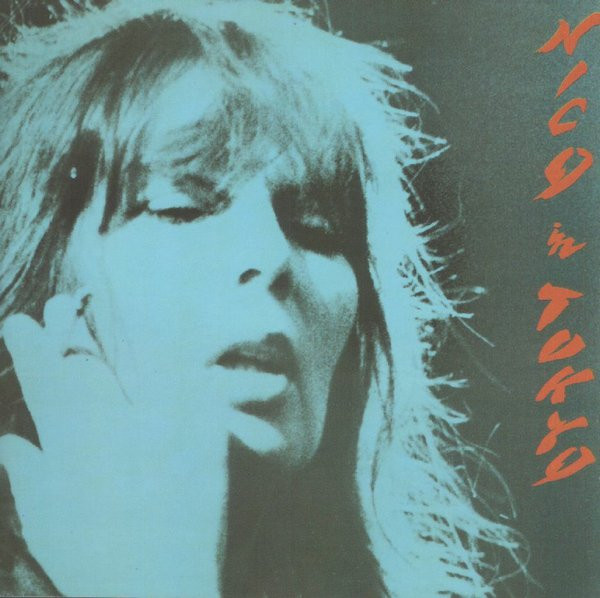

From Nico Femme Fatale compilation.

At the age of twenty-four, I decided to die. I planned it all out like a game. It was like ordering a shiny dress from a catalogue. Twenty-four was the perfect age to die.

This boy lived under a low star. Sickly spell of youth. He was hypnotised by the fragile beauty of the world. A river shining in autumn in Lancashire woods. His heart was like a castle of vanity. He wondered if people threw themselves off motorway bridges because they understood freedom like no one else.

I didn’t want to speak about myself so I wrote a story. I didn’t want to hear myself think so I sang a lonely song. Nico once said, “You don’t have to be you to be you. I see that now. All the deaths contained inside, rich and plentiful as golden black.”

You don’t have to be you to be you.

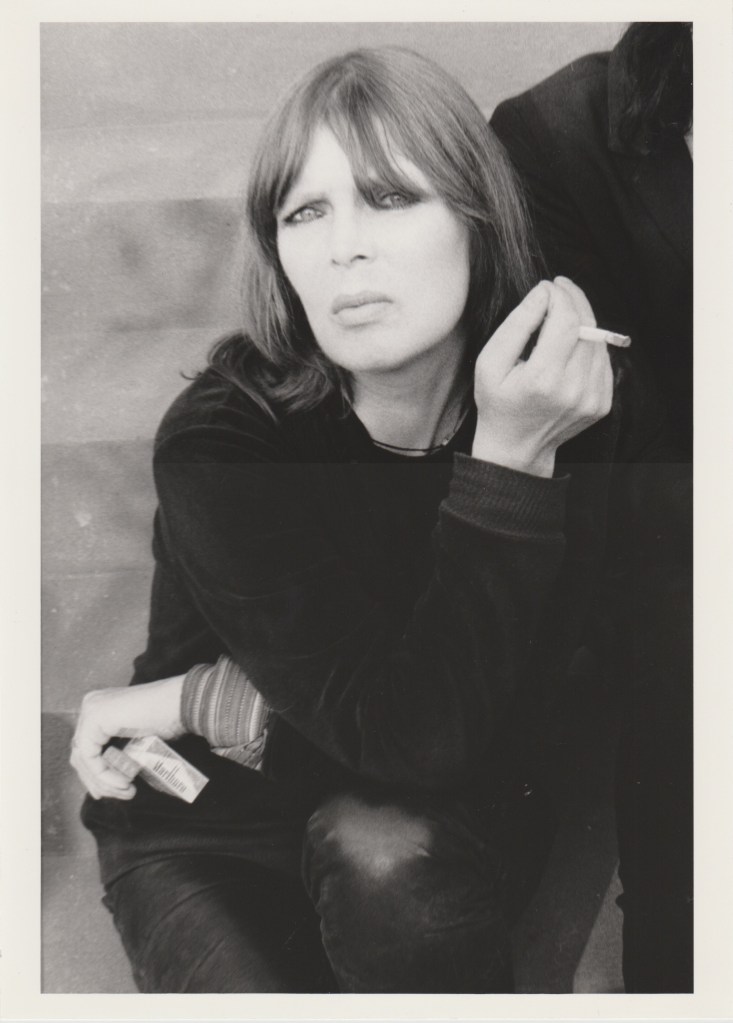

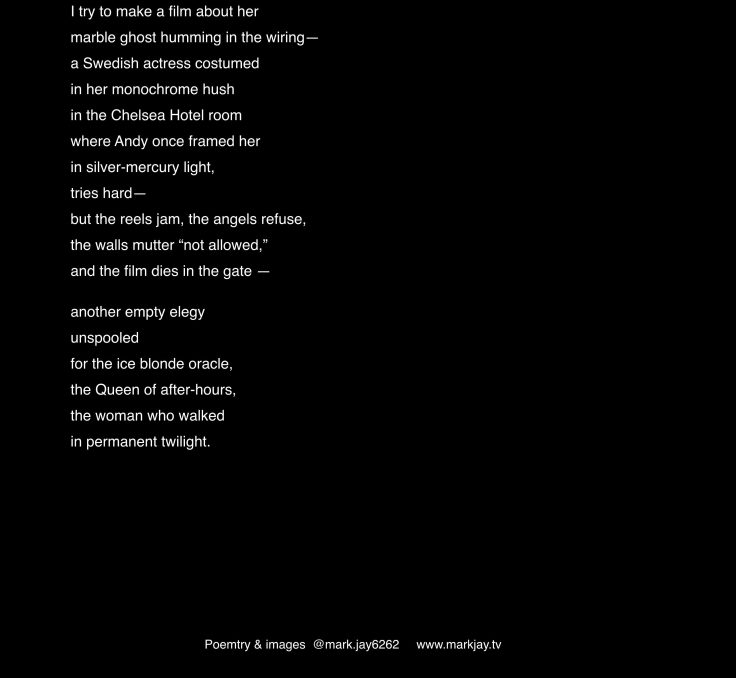

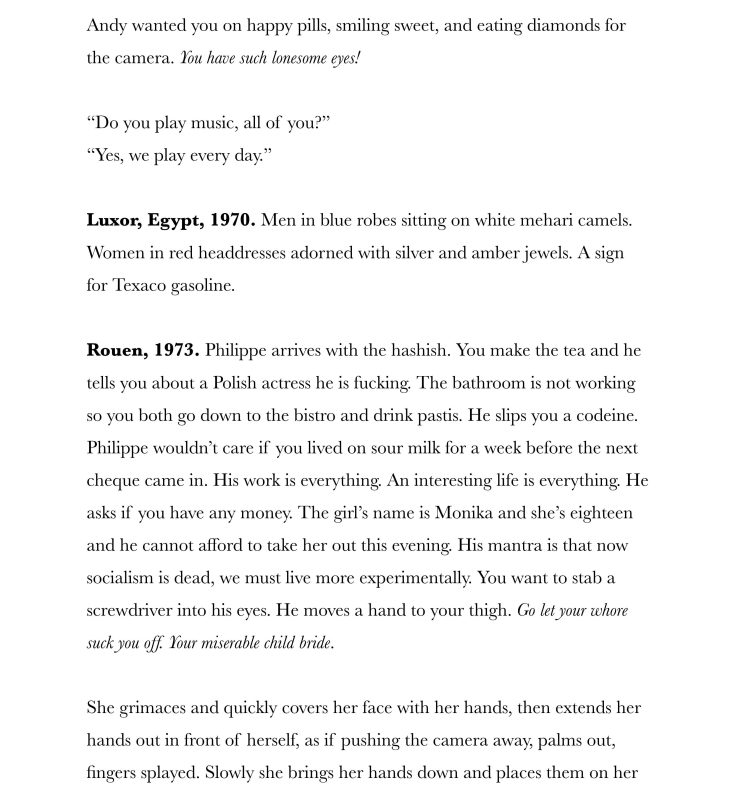

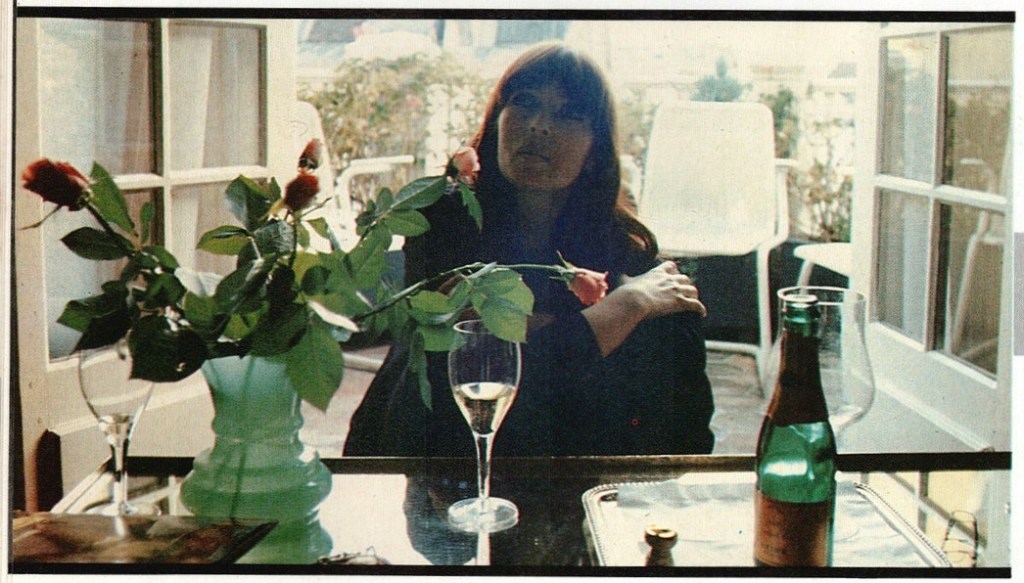

Nico by Steve Katz.

The boy, who had planned death out like a game of hopscotch, worked in an office. He wrote copy for companies about everyday objects. He spent an entire week writing about synthetic rubber tyres. Language was nothing but the accomplice of death and money. He looked outside. On the opposite side of the road was a rendering plant. They fed the carcasses of animals into enormous steel drums and boiled them into soap. When the smell began to belch into the air from endless chimneys, the workers closed the office windows. But the smell always got in and they were always complicit.

I believed I had figured out life as a magic trick. It was like when you smoke too much weed and you have the cheapest of epiphanies. It comes at you like a cartoon eureka moment. But soon, it floats away because every revelation in human history is simply a balloon in the big blue sky. I laughed. I took ecstasy pills with a beautiful friend that changed sex. We laughed harder until I threw up into the grass.

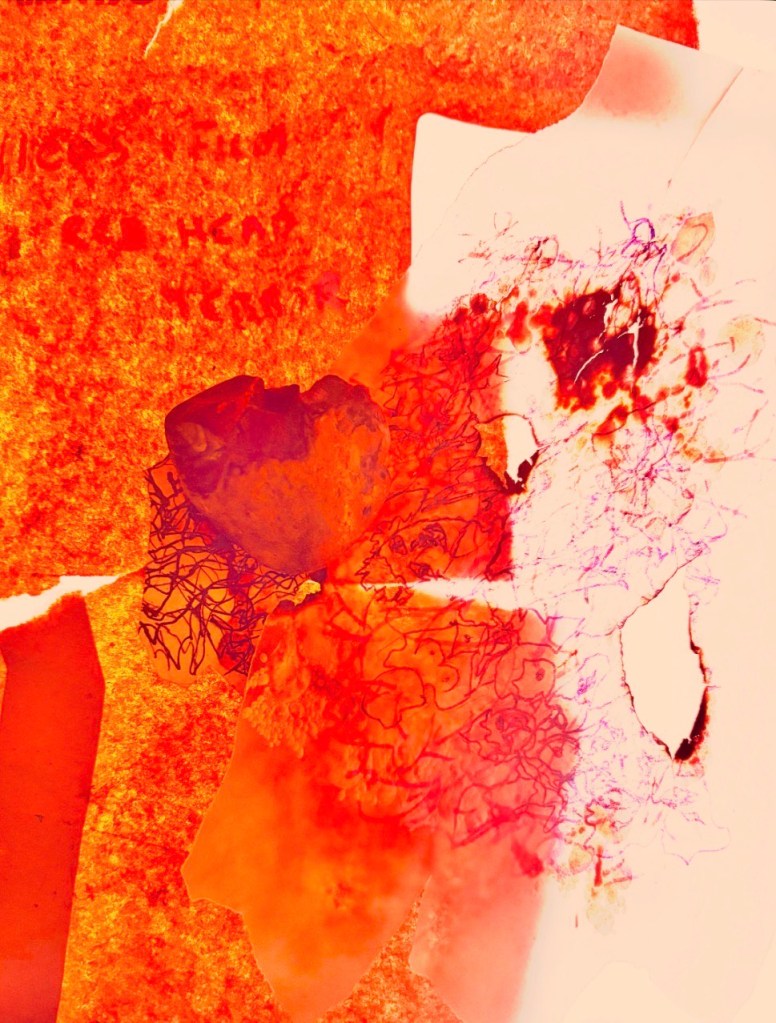

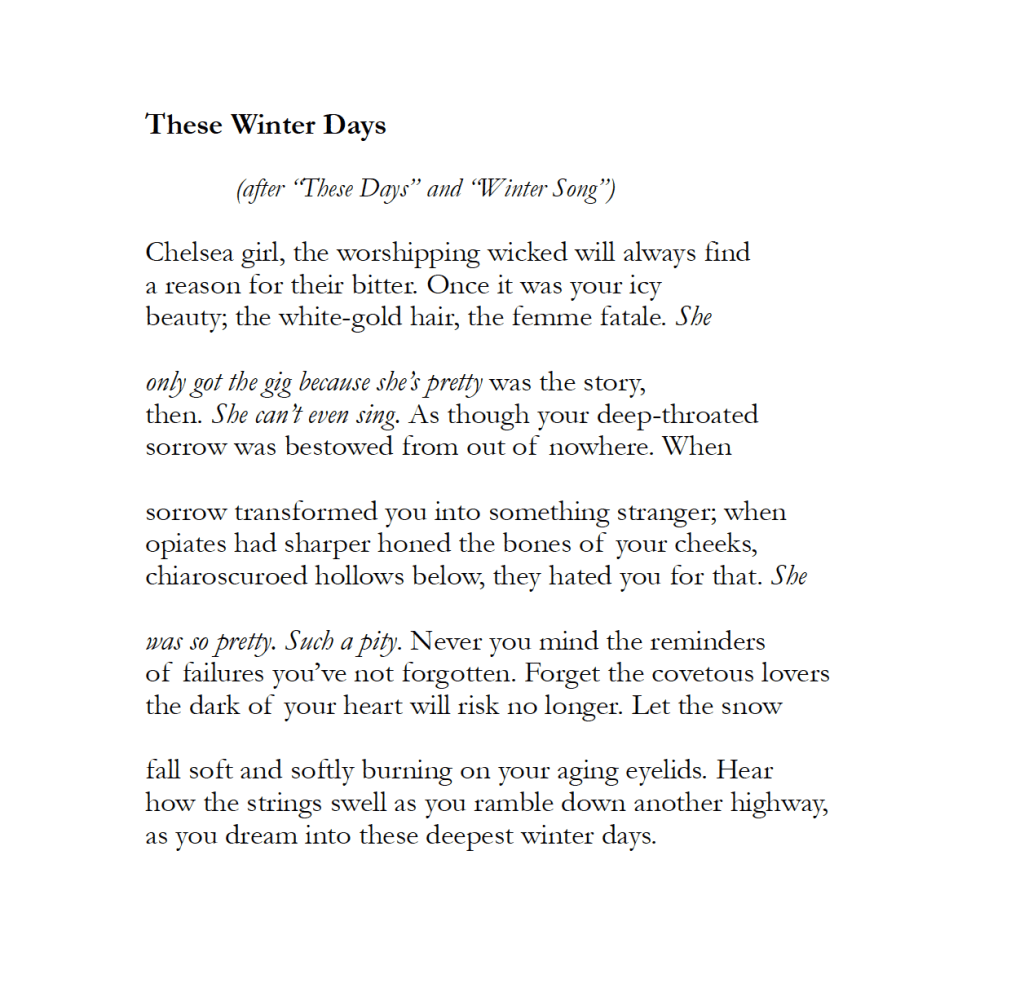

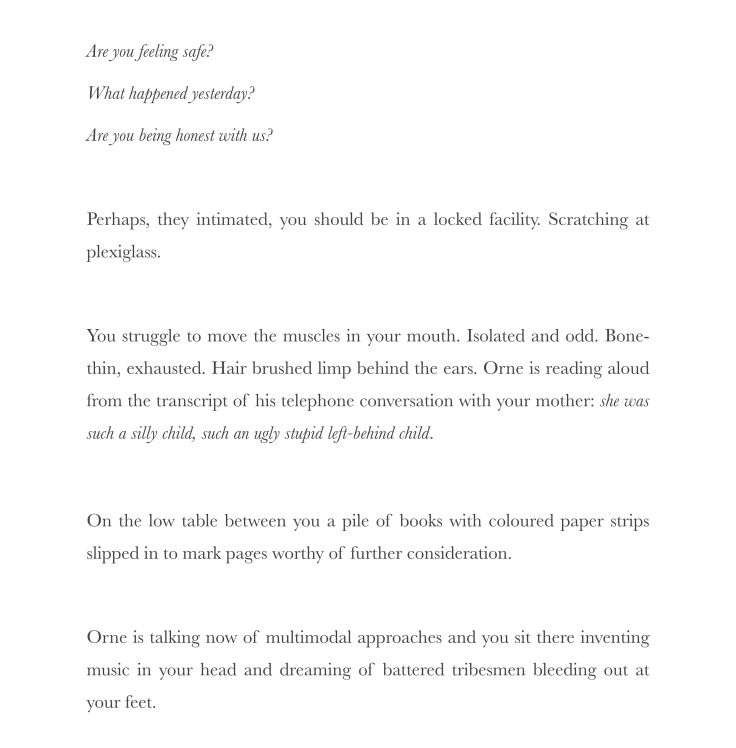

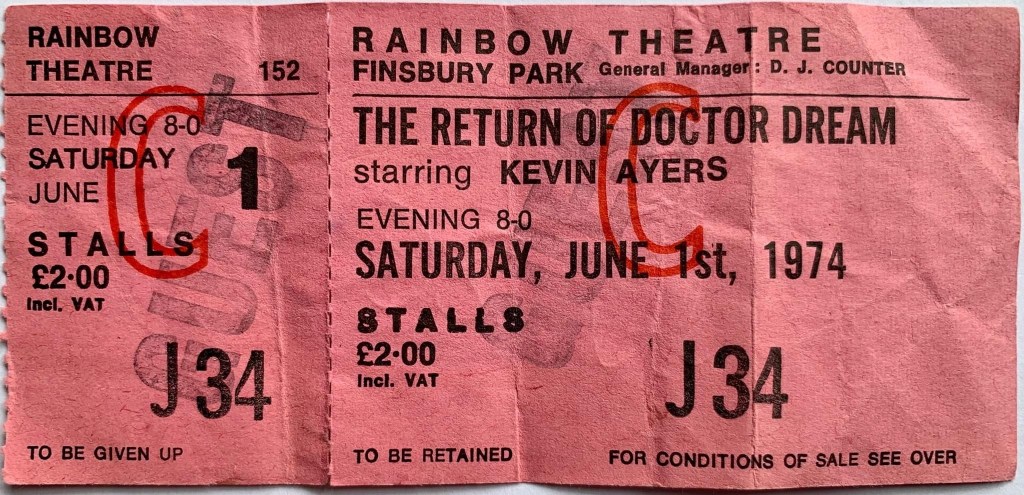

Nico in NME magazine, 1974.

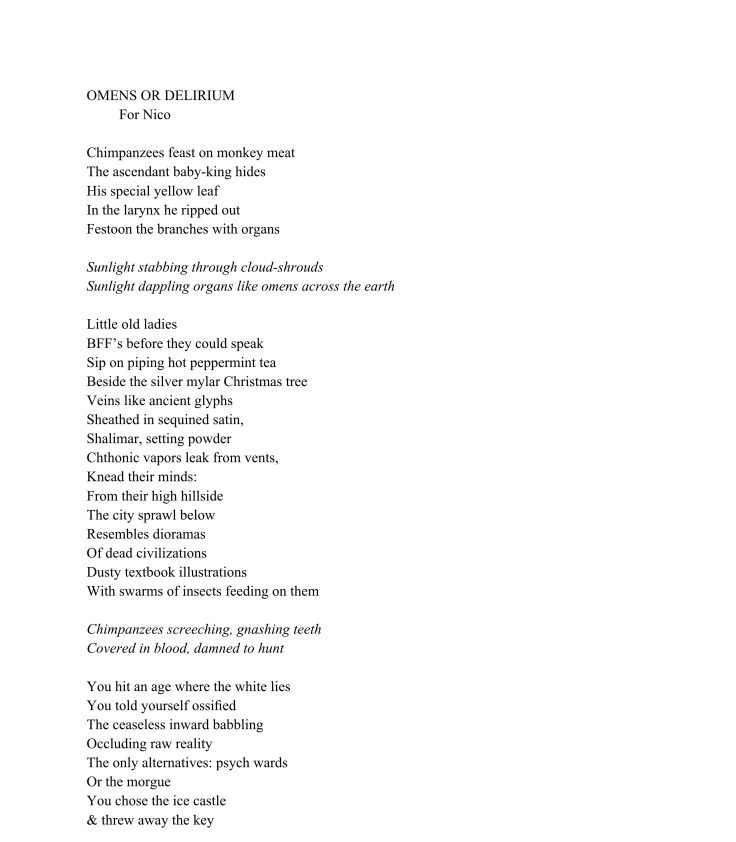

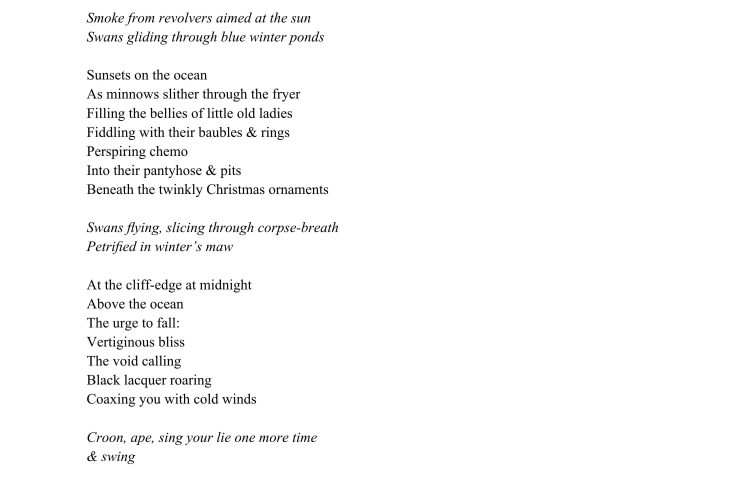

Every day, the boy would walk from the office along a canal where Victorian mills rotted into dark water. Nico was a huge fan of the Situationists. Raoul Vaneigem once wrote, “Who wants a world in which the guarantee that we shall not die of starvation entails the risk of dying of boredom?” The boy wandered past enormous cocks graffitied across the stone walls, phone numbers to unknown men in unknown towns.

I never bought albums from the dead because I had the internet by this point. There seemed no reason to line the pockets of parasitic men. I was a parasite too. Endless nights downloading poets through progress bars. Low-quality mp3s like green waxing moons. The next one on the list: Nico_The_Marble_Index. The internet was a vast séance. Nico once said, “When I sing I try to imagine I’m all alone, there’s nobody out there listening.”

Across from behind my window screen

Demon is dancing down the scene

In a crucial parody

Demon is dancing down the scene

The boy was alone. He walked through barren woods in Oswaldtwistle during winter. The saplings were covered in litter. A no-man’s land of polystyrene takeaway boxes and rainbow foil. He formed a paradise inside his own mind. He was like a demon risen from the frozen earth. His grave was covered in soiled condoms and torn-up newspaper. He watched videos on his laptop of Nico playing in a warehouse in Preston in 1982, about sixteen miles west of his current location, and backwards another thirty years. Time and space came apart inside the hand of the demon. She looked bloated on the screen with heroin and fag ash. No one is there.

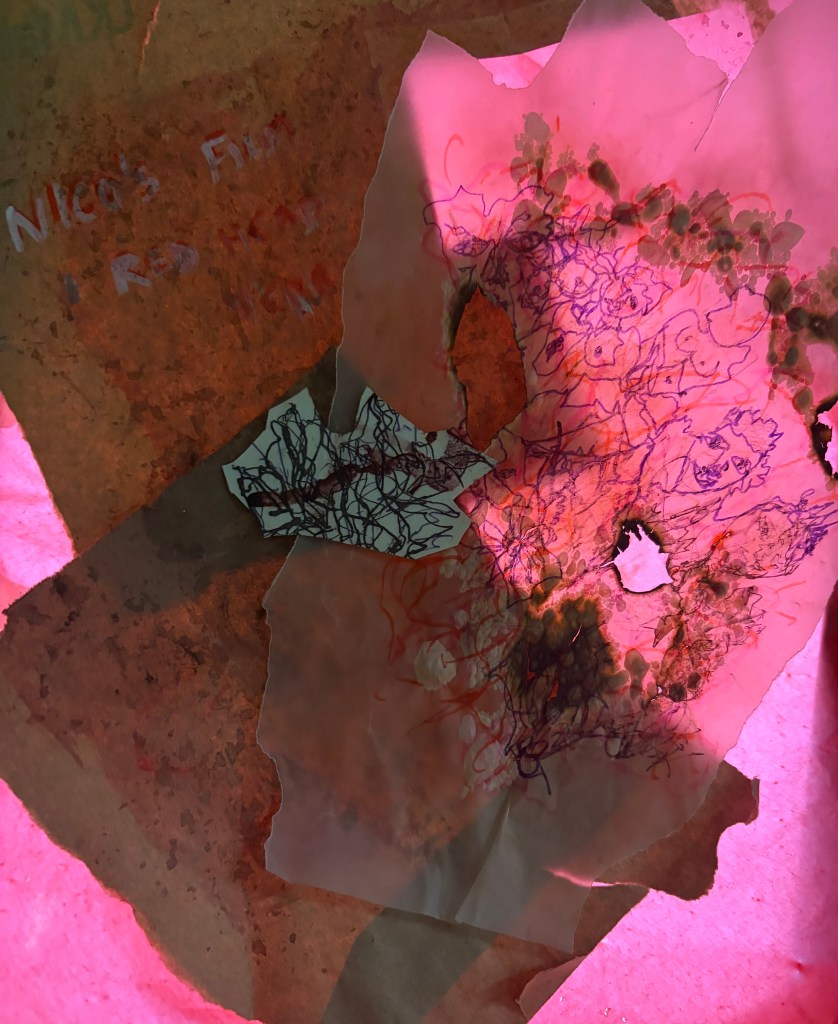

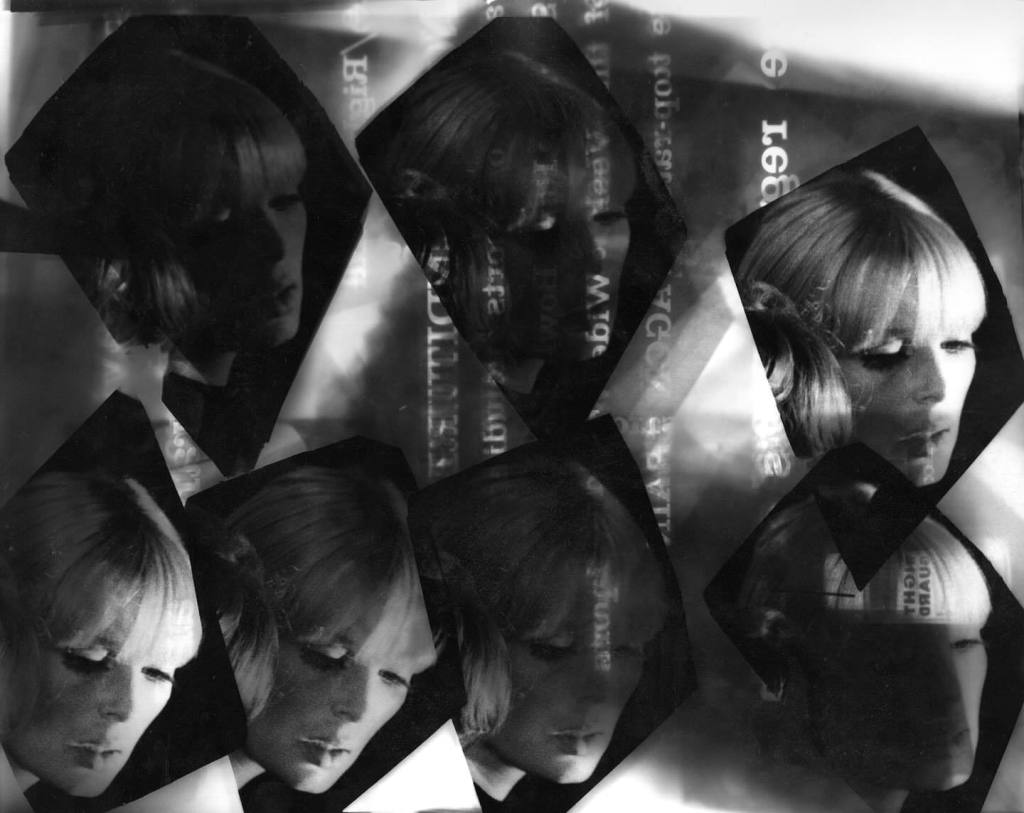

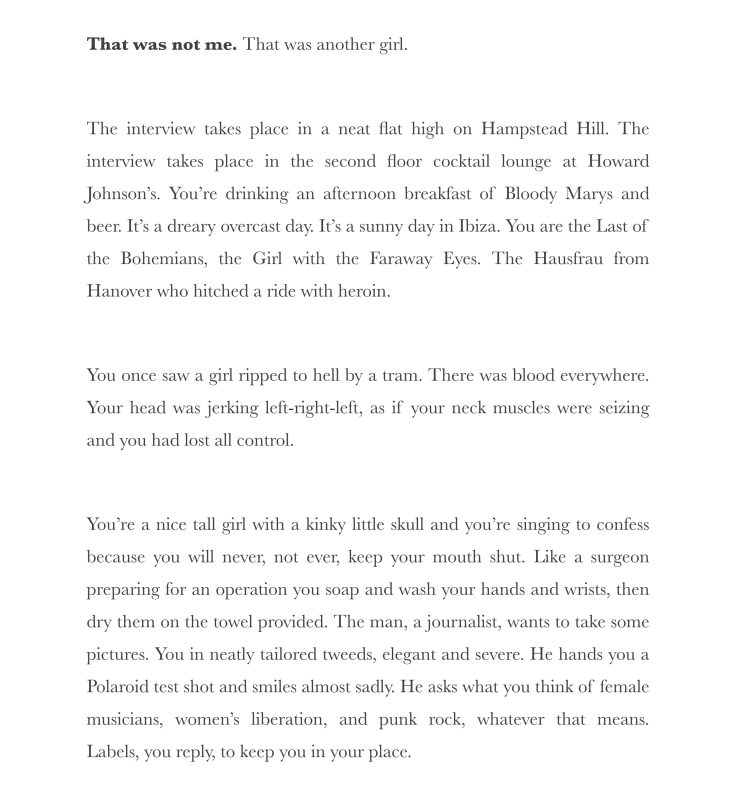

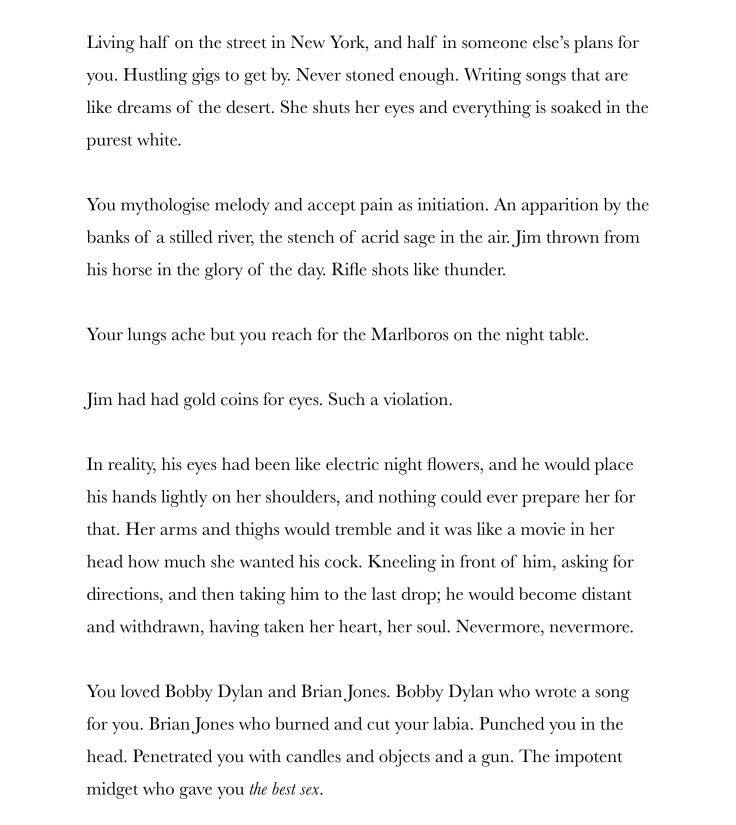

Kevin Ayers, John Cale, Nico and Brian Eno live at the Rainbow Theatre, Finsbury Park, London, June 1, 1974.

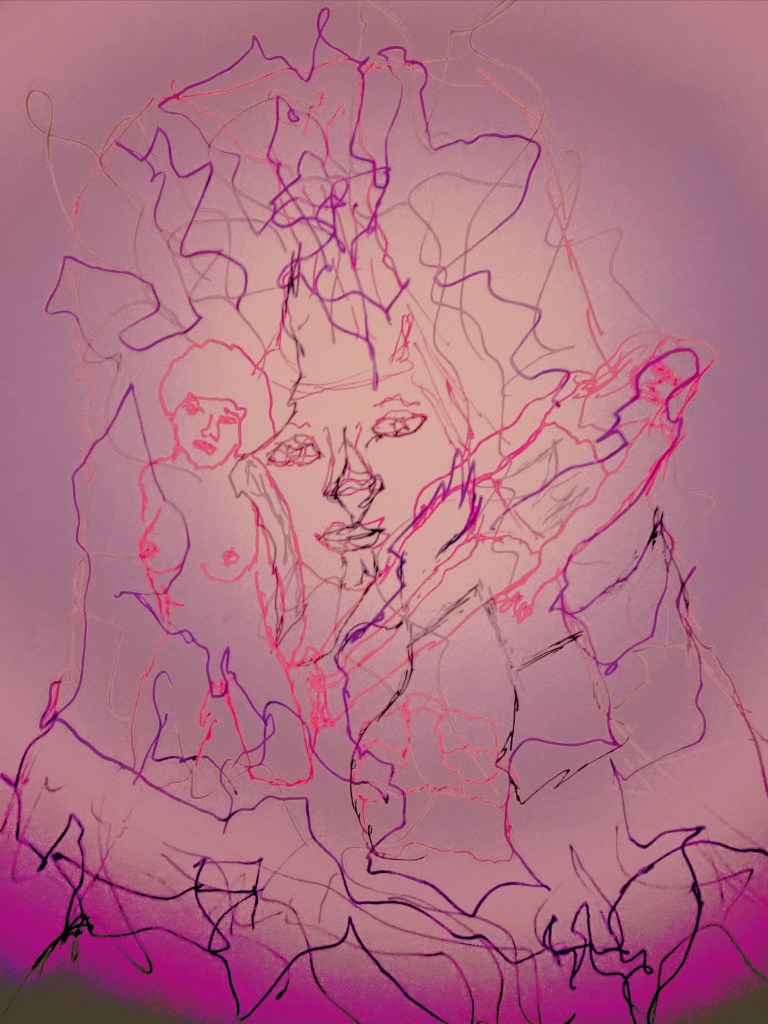

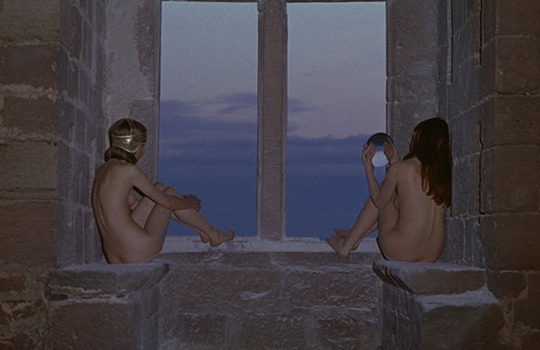

I wondered who Nico met in the Californian desert, her body unravelling from peyote like a chain of orange sickle moons. Or when she sang alone to her own shadow in a Manchester terraced house; light starting to appear between curtains as dawn stormed the crumbling walls. An emerald packet of Rizlas. A bottle of vodka shining on the windowsill. Someone’s hand turns a tarot card over on the kitchen table. The Chariot. A king holding a red glowing orb. Nico once said, “A poet sees visions and records them.” I imagined that Nico met a version of herself in the desert. She took off her clothes and led in the dust with this other version of Nico. She kissed her on the lips. And then slowly, beneath the opulent sun shining like a black flower of death, the other Nico whispered a number of secrets into her (the original Nico’s) ear. When Orpheus returned from the Underworld, he was covered in bright red earth.

A true story wants to be mine

A true story wants to be mine

The story is telling a true lie

The story is telling a true lie

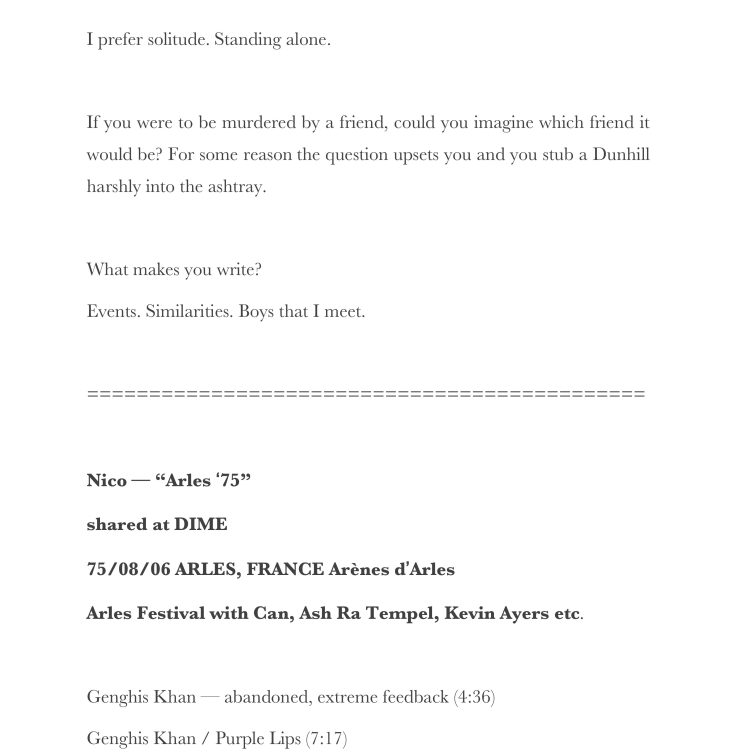

Athanor (1972) still.

The day came when the boy had planned to die. It was a dull day, just like any other. Cars streamed beneath his window. But the day simply passed him by. He wasn’t sure why. He was like a cloud or a ghost that didn’t matter. In a 1997 interview, when asked about the initially low sales figures for The Marble Index, John Cale replied, “You can’t sell suicide.”

The boy wrote down a story that was a true lie. He searched YouTube for all the comments that others had left about a dead singer and stitched them together. He stayed on stage a few moments longer as the audience grew restless. They looked at their watches and coughed and rolled their eyes. Beneath an artificial light, he approached the microphone and read a poem for Nico.

an electric blue current

a leopard in the air

an android serving macrobiotic rice

with tabasco sauce

who forgot to pay the light bill

and lived happily in the dark for a month

Ari watching his mother

putting makeup on in the mirror

illusions of our images becoming permanent

a son growing into an emperor

in a scarlet tunic

rising through a worm hole

red chariot across night sky

love is like a big cloud

a prayer or a song

raining down on you

in the middle of an apocalyptic movie

before the solar flare footage

in the forest above the water

where her grave lies

painted in crystal

she woke up at the end of time

smoked some grass

and went for a ride on her bicycle

an electric blue current

a leopard in the air

Matthew Kinlin lives and writes in Glasgow. His published works include Teenage Hallucination (Orbis Tertius Press, 2021); Curse Red, Curse Blue, Curse Green (Sweat Drenched Press, 2021); The Glass Abattoir (D.F.L. Lit, 2023); Songs of Xanthina (Broken Sleep Books, 2023); Psycho Viridian (Broken Sleep Books, 2024) and So Tender a Killer (Filthy Loot, 2025). Instagram: @obscene_mirror.